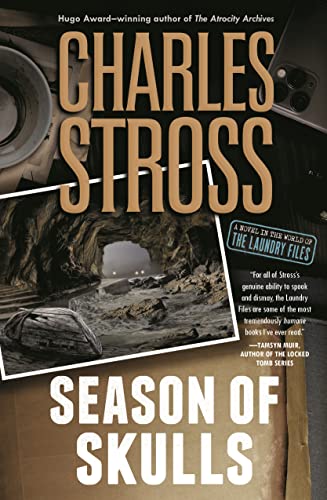

(Season of Skulls is the third book in the New Management trilogy, following on from Dead Lies Dreaming and Quantum of Nightmares. It's an ongoing story ...)

It was a bright, cold morning in Hyde Park, and a detachment of Household Cavalry was riding along North Carriage Drive in parade dress, escorting a tumbril of condemned prisoners to Marble Arch.

Imp—Jeremy Starkey, also known as the Impresario—paused beside the Peter Pan statue to watch. A tall, skinny man in his early twenties, with swept-back hair and a narrow, intense face, Imp might have been a grown-up Pan himself: a Peter Pan who'd lost his wings and grown up hard and cynical under the aegis of the New Management. He tugged his scarf with unease, then checked his counterfeit Mickey Mouse watch. He wasn't going to be late to the meeting with his sister and her lawyer if he took an extra ten minutes, he decided. Nevertheless, he drew his disreputable duster tight and hunched his shoulders. A chill wind was blowing, as if practicing to set the cartful of fettered felons swinging once they danced the Tyburn tango. It was 2017, yet some things in Bloody England never changed.

Albeit not quite everything.

Cavalry soldiers in polished silver cuirasses riding huge animals through the park were nothing new. But beside their cuirasses and high-plumed helmets these riders wore polished steel plate that covered them from head to foot, with wireless headsets, grenade launchers, and quadrotor observation drones whining overhead. Their faces were blank behind curves of bulletproof mirror glass. Their horselike steeds had sickle-bladed claws on either side of their hooves: their heads bore fanged maws and the front-pointing eyes of predators. Someone was clearly concerned about rescue attempts.

Imp shuddered and looked away from the dour procession. The distant noise of the crowd gathering around Marble Arch to watch the execution hurt his ears. He didn't want to hear the taunts of idiot rubberneckers who couldn't imagine that one day it might be them.

"Not my circus, not my monkeys," Imp muttered under his breath. Not my holiday, not my hanging, he meant. He brought his roll-up to his lips and began to inhale, but the joint had burned out, and besides, it was down to the roach. He walked across to the dog-waste bin and dumped it, then continued on his way.

It wouldn't do to keep Eve and her solicitor waiting, even though he feared the coming meeting almost as much as his own personal execution.

There's a fine line between love and hate, Eve reflected, as she watched her brother explain his mistake to the solicitor. Will she testify against me if I murder him? Eve asked herself. Is provocation a defense?

Like her brother, Eve was tall and lanky, but there the resemblance ended. She'd carefully curated her image as a blue-eyed ice queen in a designer suit. A penchant for sudden-death downsizings and the warm and friendly disposition of an angry wasp went with the territory. It had been utterly essential while she'd been Rupert's executive assistant. But now she wondered if the weight of armor she wore was worth the cost: even the lawyer seemed leery of her.

The solicitor cleared her throat, glanced at Eve for permission, then addressed Imp. "Let me get this straight, Mr. Starkey. You didn't ask your sister to confirm that she was undergoing a security clearance background check. You did not seek professional advice before initialing every page of the, um, 'nondisclosure agreement,' and the witness statement attached to it. You didn't read pages two through twenty-six. You did not ask for a translation of section thirteen, paragraphs four through six, even though it was written in medieval Norman French. Nor did you read section fourteen, the special license, which was drafted in fourteenth-century Church Latin, or the codicil stating that the contract—most of which you didn't read—was subject to adjudication under the laws of Skaro—an island in the English Channel with its own unique legal code—and that by signing you ceded your right to redress in any other jurisdiction. At no point did the messenger offer you any payment or inducement for your signature. Is that right?"

Imp nodded sheepishly. "I was very stoned. We'd just buried Dad."

Eve's cheek twitched, but her expression remained as coldly impassive as the north face of a glacier.

The solicitor clearly found it a struggle to maintain her facade of professional sympathy. "Well then. To summarize, you signed an affidavit certifying that you were the oldest living male relative of your sister, Evelyn Starkey"—the lawyer sent Eve a tiny nod that might have passed for feminine sympathy—"and signed a binding agreement to marriage by proxy, solemnized under special license as permitted by the Barony of Skaro, where the messenger acted as the representative of the groom, Lord—"

"Baron," Eve corrected automatically, then bit her tongue.

"Baron Rupert de Montfort Bigge, Lord of Skaro." The solicitor sent Eve another coded look. "Is that your understanding, too, Ms. Starkey? Or should that be Mrs. de Montfort Bigge?"

Fuck. A very expensive crunch announced the demise of the Montegrappa Extra Otto Sapphirus Eve held clenched in her fist. She dropped the wrecked fountain pen on her blotter and flexed her aching fingers. The writing instrument, carved by hand from solid lapis lazuli, was one of the most expensive pens on sale anywhere: it had come from Rupert's desk. The body might be repairable but the converter, siphon, and nib were a write-off. Emerald ink bled across the absorbent paper like green-eyed anger.

"I go by Starkey," she said, ruthlessly strangling a scream of rage in its crib. "So, what are my prospects for an annulment?"

The solicitor switched off her voice recorder and restacked the papers. "I'll need to do some research, I'm afraid. Skaroese law is a very esoteric speciality and I can't offer you a professional opinion without further work, but this is my supposition: in general a proxy marriage contracted in a jurisdiction where it is legal—the lex loci celebrationis—is recognized as binding in England and Wales. Assuming this contract is properly drafted—and there would have been no point in obtaining your brother's signature if it was not—an annulment would have to be carried out under that legal system, which means . . . " she trailed off, side-eying Eve's brother.

Imp looked up, his expression hangdog. Unlike any canine he knew exactly what he'd done wrong.

"Jeremy." Eve pointed at the door. "Scram."

"Aw—" Whatever protest he'd been forming died unvoiced when he looked at her: Eve's expression was deathly. He uncoiled from his visitor's chair and slouched doorward, shoulders hunched. "I'll just be in the staff break room."

Eve waited for the door to shut. "Finally." She congratulated herself for her restraint in not strangling him as she rubbed her forehead, heedless of her foundation. The viciously tight bun she'd put her hair into in anticipation of this confrontation was giving her a headache. "How bad is it? Really?"

"Well." The solicitor slid her folio sideways, out of Eve's direct line of sight. "If your hus— if Baron de Montfort Bigge is dead, and if you can obtain a death certificate, then you're off the hook. Once you obtain a death certificate it's all done and dusted and you can remarry if that's what you want to do."

"Assume he's not dead, just missing. No body, but no proof he's alive either."

"Then you need to either provide proof that he died or run down the clock. You can apply for a declaration of presumed death after seven years in the UK, and Skaroese law probably says the same—I will confirm that later—so, six years and nine months from now. In the meantime, if he's missing his continued existence is not an impediment to you unless you wish to marry someone else—" The solicitor raised her eyebrow. "Or is it?"

Eve's cheek twitched again. "The law takes no account of magic. Or aliens and time travel, for that matter."

"Magic—" The solicitor was momentarily nonplussed. Eve hoped she wasn't one of the materialist holdouts. The arrival of the New Management (not to mention an elven armored brigade rampaging through the Yorkshire Dales, vampires taking their seats in the House of Lords, and superheroes breaking the sound barrier as they sped to intercept airliners) had sent many people into reality-denying madness. They called the casualties of the Alfär invasion crisis actors and used elaborate conspiracy theories to explain the Prime Minister's penumbral darkling and appetite for human souls. It was all a Russian disinformation scheme, a viral pandemic that induced delirious hallucinations, or a conspiracy of (((cosmopolitans))). "Seriously?"

"Contracts have implications for ritual magic." Eve let her smile slip, allowing her feral desperation to shine through. "If he's not dead then as long as the marriage is legally binding, I'm—" She shook her head. "Let's not go there."

Rupert had imposed a geas on her—an obedience compulsion—as one of the initial conditions of her employment. She'd thought it contemptibly weak at the time, and he'd never tried to use it, so she'd never tried to break it. He ensured her compliance through traditional means—gaslighting and blackmail—and she was completely taken in by his pantomime of sorcerous incompetence. When she finally discovered the proxy marriage certificate after his disappearance, it became clear that he'd known exactly what he was doing with the geas: the bumbling was a malevolent act.

Skaroese law was based on medieval Norman law, but hadn't been updated much since the fourteenth century. The Reformation had passed it by, and it still embodied archaic Catholic assumptions. Skaroese marriage recognized the archaic status of feme covert: a married woman was legally of one flesh with her husband, a mere appendage with no more right to own property or express an opinion in court than his dressing table or his horse. A geas given additional strength by such a marriage contract was only distinguishable from chattel slavery because the rights it granted her husband were nontransferable.

Since discovering the document, Eve had awakened in a bath of cold sweat at least three times a week, stricken by the conviction that her scheme to rid the world of Rupert had failed.

The solicitor continued to lay out the dimensions of her prison. "As the marriage was contracted under Skaroese law, you should apply for an annulment in that jurisdiction." (And I can bill for more hours, Eve mentally added, a trifle unfairly.) "You'll need to obtain a decree of nullity from the diocese, essentially a declaration that the marriage never existed. That'd be the diocese of Skaro, which is the first stop. Have you spoken to your priest?"

"Ah, there might be a problem with that." Skaro had been taken over by the Cult of the Mute Poet a generation ago. The worshippers of Ppilimtec, god of wine and poetry, did not play well with other religions—and Rupert was its bishop. There had been no other church on Skaro for decades. "I might be able to get one, though." If I offer to cover the repair bills, pay for the exorcism and reconsecration, and fund a stipend for the priest and his bodyguards, surely the Catholic Church would assign someone? It wasn't as if she was a believer herself, but her mother had dragged her through baptism and confirmation in her childhood, so no loophole there. As for the bodyguards, Ppilimtec was a jealous deity. Annulment was going to be expensive, but as she had effective control of the Bigge Organization, money was the one thing she was not short of.

"Then that brings me to another question." The solicitor paused apprehensively. She tugged at her jacket, brushed imaginary lint from her lapel, screwed up her courage, and asked, very quickly, "In strictest confidence, Ms. Starkey, have you ever engaged in sexual intercourse with Baron Skaro? Either before or after the proxy marriage?"

Eve shook her head. "No, I never had sex with—" She paused for a double take. "Does telephone sex count?"

"Tele—" The solicitor gave her a blank look. "Could you clarify that?"

No, Eve thought, but her mouth answered regardless. "Rupert would phone me at any hour of the day or night—I was his executive assistant and PA, both hats at the same time—and treat me like a phone-sex worker. The only way to get him to shut up was to tell him a pornographic bedtime story until he finished wanking." She could feel her cheeks glowing. "It was workplace sexual harassment, but I couldn't quit the job—"

Eve felt something cold and moist on the back of her left hand. She glanced down with carefully concealed distaste. The solicitor had laid a hand on her wrist: the woman wore an expression of heartfelt sympathy. "I understand completely," she said. Show me where the bad man touched you. "I'm pretty certain the Catholic Church doesn't count coerced telephone sex as intercourse for purposes of obtaining an annulment." She smiled apologetically.

"In general, the three requirements for a valid marriage in canon law are that the couple married freely and without reservation, that they love and honor each other, and they accept children lovingly from God. None of those apply to you. I see absolutely no way that these papers"—she tapped her folio—"can be construed as anything other than an attempt to bypass the intent if not the letter of the law, so I think it ought to be possible to convince a parish priest to petition the diocese tribunal for an annulment on your behalf. It normally takes eighteen months or so to obtain one, with the right supporting documents. But as I said, I need to research the minutiae of Skaroese law." She rose. "Is that everything you wanted me to cover?"

Eve suppressed a brief impulse to bang her head on the table. Eighteen months. Eighteen months of maximum vulnerability, eighteen months of night terrors, eighteen months of uncertainty and paradox. "It'll have to do," she said tightly. "If there's anything I can do to speed the process up—anything, whatever the cost—be sure to let me know." She stood and led the lawyer to the door of her office. "Day or night," she emphasized, showing her out.

Rupert de Montfort-Bigge, Baron Skaro, had been missing for nearly three months, lost in the dream roads that connected other lands, times, and universes. He'd been trying to retrieve a cursed tome that Eve had procured on his behalf, and creatively mislaid.

If he was still alive, Rupert would be in his late thirties but appear a decade older. He'd chosen his grandparents well: born to a birthright of privilege and wealth, he'd had the freedom to squander everything fate handed him and to write it off as a learning experience.

After schooling at Eton he'd studied Philosophy, Politics, and Economics at Oxford. While at university he'd joined the Oxford Union, a debating society and the usual first step toward a Conservative junior minister's post. He'd also joined other, less savory clubs, and a particularly damning video shot at a boisterous underground dining club had surfaced when his name was put forward for a parliamentary seat. Bestiality was a crime, necrophilia was a crime . . . bestial necrophilia in white-tie and tails fell into a Twilight Zone loophole that Parliament had failed to criminalize, but the candidate selection committee nevertheless felt it best to err on the side of caution. (Questions about his vulnerability to blackmail had been raised.) Rejected by politics Rupert sulkily slouched off to the City, apparently intent on dedicating the rest of his life to the pursuit of drugs, depravity, and wealth beyond the dreams of avarice.

Had Rupert been just another chinless wonder with a penchant for Bolivian nose candy, high finance, and the English vice, his subsequent trajectory would have been undistinguished and short. But somewhere along the way Rupert conceived a plan. The precise details were obscure—he fully confided in no one after the Dead Pig Affair—but this much was clear: Rupert still harbored political ambitions, but not parliamentary ones. His new path to power centered on the secret cult he had joined before he was sent down.

Strange faiths that practiced unspeakable rites were springing up everywhere these days, growing in numbers and spreading like clumps of horrifyingly poisonous toadstools as the power of magic waxed. Rupert ascended rapidly through the priesthood of the Mute Poet, using their sacramental rites to obtain investment guidance from his unholy patron. And he made use of every available edge, from option trades to obsidian sacrificial axes, to bloat his fortunes and selectively evangelize the faith.

The Cult of the Mute Poet presented itself to the public as a somewhat eccentric Christian sect: the Church of Saint David, patron of poets. Its inner circle, however, worshipped Our Lord the Undying King, Saint Ppilimtec the Tongueless, who sits at the right hand of Our Lord the Smoking Mirror. Fifteenth-century conquistadores in the New World had witnessed the rites performed by Nahua priests and been impressed by the results: so they had copied their practices and applied them to their own corrupted saints. When you recited the right phrases and made sacrifice appropriately, things that dwelt in other realms might listen and lend their will to your ends—even if they were not the beings toward which your pleas were directed. And it wasn't as if the Catholic Church wasn't syncretistic by design—it was right there in the name—so what, if it required a little human sacrifice to energize the power of prayer?

The Church of the Mute Poet was not the worst of the sanguinary cults that festered beneath the aegis of the Inquisition. Most of the most gruesome offenders were stamped out before the return of magic. In any case, all were overshadowed by the New Management, the government of the Black Pharaoh—N'yar Lat-Hotep—the Crawling Chaos Reborn. But the followers of Ppilimtec the Tongueless survived, alongside certain others. They thrived under Rupert's Machiavellian leadership, building congregations and attracting converts, and with every victim sacrificed and each service of worship conducted, Rupert funneled power to his Lord.

In return he received the benefits accrued by a high priest.

But to what end?

Eve neither knew nor truly cared. She just wanted to be free of his demands. She'd risen to a position of power almost absentmindedly, unaware of the proxy marriage that made her his magically enslaved minion (and, inadvertently, his heir). Discovering that as his wife or his widow she controlled his hedge fund and web of offshore investment vehicles was a pleasant bonus, but in truth, Eve hadn't tried to kill him for the money.

Eve had ambitions of her own. She was bent on revenge against another cult, the Golden Promise Ministries, who had taken the life of her father and the mind of her mother. Unfortunately, cleaning up the mess Rupert had left behind—his followers had been up to their eyeballs in foul schemes—was sucking all the air out of the boardroom and leaving Eve no time for her own plans.

Then, as if that wasn't bad enough, she'd come to the attention of very important people.

Two weeks into the new year—four weeks after she led her security team to Castle Skaro and interrupted her husband's followers, who had been attempting to sacrifice a family of superpowered children in order to summon Rupert's shade from wherever he'd been banished to—Eve received a visit that she had been both expecting and dreading for some time.

Taking control of Rupert's business empire in his absence was one thing (she'd already deputized for him over a period of years). But his occult empire was another matter entirely. His followers were numerous and murderously devoted to their Lord. He'd sent them instructions via an after-death email delivery service: Eve dared not read her incoming messages without first subjecting them to three layers of filtering, just in case he tried to Renfield her from beyond the grave.

At least she'd cleaned house in the security subsidiary. She'd had to, after a failed assassination attempt. Sergeant Gunderson had proven to be trustworthy, although she hadn't managed to extract any useful intelligence from Eve's would-be killer before he choked himself to death on his own tongue. And Eve's own basement den was safe, although she used Rupert's ostentatious luxury suite upstairs for receiving visitors.

She was reviewing the quarterly figures from the Bigge Organization's defense procurement subsidiary when her earpiece buzzed. "Starkey," she snapped irritably. "I'm on do not disturb for a reason. Is the building is on fire?"

"Ma'am, you have a visitor waiting in reception," said the receptionist who'd interrupted her spreadsheet-minded musing. Something in her tone put Eve on notice that perhaps the building was on fire, figuratively speaking. "She's from the House of Lords and she's asking for you by name."

Eve shuddered: this was absolutely a metaphorical house fire. "I'll be right with you," she said, much more politely, and hung up.

Eve secured her laptop then pulled her heels on and checked her makeup, clearing the decks for action. Those people—the House of Lords—didn't exactly pay house calls: they had minions to do that sort of thing. And a mere minion wouldn't turn up unheralded and expect to see the boss. So, while it might be something minor—a social call on Baron Skaro's widow, for instance, an invitation to discuss Rupert's tax returns, a request for a cup of sugar—Eve was fairly certain that it wasn't minor. And that meant she had to get her game face on. After all, the sequel to the curse may you live in interesting times was may you come to the attention of very important people. And they didn't come much more important than the New Management of Prime Minister Fabian Everyman.

Under the New Management, the House of Lords wasn't just a sleepy debating club for aristocratic coffin dodgers. In 2007 the House had been reconstituted as a serious, albeit unelected, revising chamber that handled a lot of lawmaking and committee work on behalf of the government. Then when the New Management arrived, it had been given executive responsibilities as well. In particular, matters of thaumaturgy, necromancy, and demonology now fell within the ambit of what had once been known as the Invisible College, a secretive body originally established under the governance of the Star Chamber.

Eve was not one to overindulge in Star Wars references, but as she entered the ground-floor lobby area she sensed a disturbance in the Force. It felt as if a thunderstorm was about to break: the doorman, the receptionist, and the duty security guard had frozen like rabbits before a hungry fox, all of them paralyzed and unable to look away from a woman of indeterminate age. Her glossy black hair was as tightly controlled as her bearing, and her suit was vintage Chanel, Eve guessed. And at her shoulder stood a man whom she recognized immediately as ex-military, quite likely ex--special forces.

"You must be the Ms. Starkey I've been hearing so much about." (Eve felt a treacherous flash of relief at her visitor's use of her real name. Way to make a good first impression.) The woman smiled as she extended her gloved hand. "Johnny, introduce me," she told her bodyguard.

"Yes, Du— Your Grace." Despite being a mountain of muscle in a suit of sufficiently generous cut to conceal a small arsenal, and despite having a vestigial Scottish burr, the bodyguard showed dangerous signs of sentience. "Ms. Starkey, please allow me to introduce Her Grace, Baroness Persephone Hazard. Her Grace is the Deputy Minister for External Assets."

"Please, call me Seph," said the baroness. "I think it's long past time we had a little talk, don't you agree?" She met Eve's eyes, smiled, and gazed deep into her soul.

Eve's brain froze as words failed her. She had an apprehension that she was in the presence of a great predator: perhaps a triumphant witch-queen, or the viceroy of Tash the Inexorable in a broken Narnia where Aslan had been crucified before the sacrificed corpses of the Pevensie children. But then the ward she wore on a charm bracelet around her left wrist grew hot, the sense of imminent damnation began to recede, and she blinked, broke eye contact, and regained self-control. A hot prickling flush of embarrassment and anger spread across her skin. Baroness Hazard was not only a practitioner but a really strong one: stronger than Eve, stronger than her father, stronger than Rupert. And Persephone had just rolled Eve, spearing through her defenses before she realized she was at risk.

But Eve was still alive. Which meant the baroness wanted something from her, not just her skull on a spike. So the situation was probably still salvageable? The gridlock behind her larynx broke. "Follow me," she said hoarsely, then turned and retreated downstairs to her office. She heard footsteps following her: the baroness's heels and Johnny's heavier tread.

Eve's office was much smaller than Rupert's, but it was less prone to interruption and Eve had ensured it was secure. She sat and waved at the seats opposite. The visiting sorceress sat, while her bodyguard stepped inside and closed the door, then took up position beside it. He stood at parade rest, his unblinking gaze fixed on a spot a meter behind Eve's forehead. Eve raised an eyebrow at the baroness. "Is he . . . ?"

Seph nodded. "Johnny has my back," she said with complete assurance.

"Always," he rumbled, a hint of warning coloring his voice.

Eve fought the impulse to hunch her shoulders. "I'm sure your time is very valuable," she said, smiling but keeping her teeth hidden. "How may I help you?"

Seph crossed her legs, smirked, and asked, "What do you know about the Cult of the Mute Poet?"

Eve felt as if her life ought to be flashing across her vision at that moment. It didn't happen in real life, but if it did this was the right time for it to happen, wasn't it? The baroness was clearly not asking her to read back the Wikipedia article on the god Ppilimtec, Prince of Poetry and Song. There was another game in play.

She took a deep breath, then very carefully said, "I am obedient to His Majesty the Black Pharaoh, N'yar Lat-Hotep, wearer of the Crown of Chaos. I will swear any oath required of me to confirm my loyalty. Is that why you're here?"

The baroness cocked her head to one side. In the distance, Eve felt rather than heard the rumble of the breaking storm. "That is an acceptable start, but I fear I was insufficiently precise. Let me amend my question. What is your connection with the Cult of the Mute Poet?"

Eve licked her desert-dry lips, then began to explain everything: from her mother's fall into a decaying orbit around the black hole of the Golden Promise Ministries to her own vow of revenge, to her recruitment by Rupert, the subsequent degradation and depravity, the proxy marriage she had only found out about the previous month, and finally her discovery that Rupert was in fact not only an organized-crime kingpin but the cult's bishop or high priest and that she was, in the eyes of Skaroese law, of one flesh with him. Midway through her confession her phone rang. She muted it and carried on. The baroness nodded when she enumerated her visits to Skaro and to the church in Chickentown, described the bloody carnage in the conference room and the underground chapel, then confessed her own desperate anxiety about the question of Rupert's existence. It was, she felt, as if she had lost control of her own tongue—but that was impossible, wasn't it? Rupert's office was thoroughly warded, she herself was warded, she'd know if—

Finally, the baroness spoke.

"I find it interesting that your former employer"—Eve felt a stab of gratitude that she said former: it implied a certain distance—"left werewolves in your security detachment. And even more interesting that the survivor suicided."

"Werewolves?"

"Not actual shape-shifters, skinwalkers don't exist, you can trust me on that! I mean undercover loyalists with orders to conduct assassination or terror operations on behalf of their absent leadership. It's something you usually only see with State-Level Actors." Seph paused, then looked thoughtful. "Was Rupert an SLA? In your opinion."

"Not on the same level as His Majesty, but"—she recalled the paperwork from his office, under the battlements of a Norman fortress—"obviously he has his own jurisdiction, doesn't he? Held in feu as a vassal of the Duke of Normandy." Unless somehow one of Her Majesty's ancestors' law clerks had fucked up and—no, don't go there, Eve thought, don't even think that thought. "He had a surprising number of heavily armed goons, connections to shady arms dealers, annual revenue measured in the billions of euros, and his own cult, so yes, I think you could reasonably make a case that he was a State-Level Actor. Or at least that he fancied himself as a kind of occult Ernst Stavro Blofeld." (The kind of necromantic Bond villain who liked to relax by hunting clones of himself on a private island, or extorting trillion-dollar ransoms from the United Nations in return for not repopulating New York with dinosaurs.) "But then he died"—hopes and prayers—"and his mess landed in my lap."

"Jolly good, Ms. Starkey."

Persephone's smile flickered like heat lightning, liminal and deadly, and Eve had a sense of barely constrained magic aching for explosive release. The baroness was clearly of human origin, but sorcerers of such power rarely stayed human for long. Either the Metahuman Associated Dementia cored them from the inside out, or they made a pact with the deadly v-symbionts that thrived in the darkness. Or they transcended their humanity in some other arcane manner: it mattered not. What mattered was that whichever path they chose, they trod the Earth like human-shaped novae and left blackened footsteps in the molten rock, until they finally burned out and collapsed into some incomprehensible stellar remnant of proximate godhood. Persephone was still human for the time being, but Eve uneasily apprehended that she was sharing her office with a polite but not entirely tame nuclear weapon.

"Understand that I speak now as the mouthpiece of the New Management. It pleases His Majesty," Persephone continued, and there was an echo in her voice as if a god was taking note of her words and nodding along gravely, "for you to do as you wish in the matter of the Church of the Mute Poet." Which, Eve interpreted, meant she'd just been handed enough rope to hang herself with—and not a centimeter more.

Then Persephone continued, in more human tones, "But are you absolutely certain that Rupert de Montfort Bigge is permanently dead?"

Eve froze. "I sincerely hope so!" she burst out.

"You didn't actually see his corpse, did you?" Persephone had the effrontery to look sympathetic, damn her eyes.

"I didn't," Eve confessed. "But I don't see any way he could have survived if he followed my directions. And he had no reason not to." She flinched as an entire herd of black cats padded across her open grave.

"Well." The distant shining darkness entered Persephone's gaze again. "Let it be understood by all that Rupert de Montfort Bigge, Baron Skaro, is hereby de-emphasized by order of the New Management. Should he set foot on these isles again, he shall find no sanctuary in the House of the Black Pharaoh. He is outside the law, and though he may live or die, none shall give him aid and comfort. Furthermore, the New Management decrees that pursuant to the marriage contract executed by the outlaw Baron Skaro in her absence, being his lawful wife, Evelyn Starkey is recognized as his sole heir and assignee."

Persephone paused. It was just as well: Eve was on the verge of hyperventilating and needed an entire minute to regain control once more. Eventually the black fuzz at the edges of her vision receded.

"I, uh, I . . ." Eve couldn't continue.

Persephone continued, back to speaking in her own voice, "You are summoned to attend the Court of the Black Pharaoh within the next three months—you will receive instructions by post in due course—at which time you will swear allegiance to His Dread Majesty." Or else was a given. "At that time His Majesty may choose to leave you be or dispose of you in accordance with his wishes." Eve found it hard not to flinch again. "That's not necessarily detrimental to you—the government has numerous executive posts to fill and a shortage of competent vassals. If you play your cards right you may prosper, never mind merely surviving. But. Terms and conditions apply, as they say. Your complete submission is a nonnegotiable and absolute requirement of the New Management: no ifs, no buts."

Translation: You're drafted! Eve steeled herself and nodded. "What else?" she asked.

"As heir to Baron Skaro's properties, rights, and duties, His Majesty holds you responsible for any future transgressions by the Cult of the Mute Poet. The buck, as they say, stops here." The baroness pointed a shapely finger at the desktop in front of Eve. "But the New Management is not hanging you out to dry. You are welcome to call on me for advice and guidance, and if at any time you feel you really can't cope, you can petition to be relieved of your responsibilities. That's a card you can play only once, but it's better than ending up with your head on a spike."

Eve translated mentally: We're taking over your operation but we're keeping you on as Corporate Vice President for Cannibal Club Poetry Slams, unless you fuck up so badly we decide to execute you. She nodded, her mouth dry. "Is that all?" she asked.

"Not quite!" Baroness Hazard beamed at her. "There's one last thing. His Majesty appreciates tribute, as a gesture of submission on the part of new vassals. In view of the uncertainty surrounding the postulated death of your husband, and in order to prove beyond reasonable doubt that he is dead, I would strongly advise you—and I am sure this aligns perfectly with your own preferences—to gift His Majesty with the head of the outlaw Rupert de Montfort Bigge when you are presented at court. It would be a perfect addition to His Majesty's cranial collection, and it would be one less thing for everyone to worry about—both His Majesty and yourself, if you follow my drift."

With that, she rose. "Welcome to the team, Evelyn. I look forward to working with you in future. Goodbye!"

The year is 2017, and in a few months' time it will be the second anniversary of the arrival of the New Management.

Welcome to the sunlit uplands of the twenty-first century!

One Britain, One Nation! Juche Britannia!

Long live Prime Minister Fabian Everyman! Long live the Black Pharaoh!

Iä! Iä!

(Now that's the spirit of the age, eh what?)

Magic, in abeyance since the dog days of the Victorian era, has been gradually slithering back into the realm of the possible since the 1950s. Wartime work on digital computation—the works of Alan Turing and John von Neumann in particular, the codification of the dark theorems that allowed direct manipulation of the structure of reality—turn any suitably configured general-purpose computing device into a tool of hermetic power. Cold War agencies played deep and frightening head games with demons at the same time their colleagues in rocketry and nuclear physics reached for the stars and split the atom. Old dynasties of sorcerers and ritual magicians—those who practiced magic as an intuitive art rather than methodical science—have gradually regained their skills and rediscovered their family secrets.

The onslaught of microelectronics cannot be described as anything less than catastrophic. For five decades, Moore's Law has driven a relentless exponential increase in performance per dollar, as circuits grow smaller and engineers cram more transistors onto each semiconductor wafer. Minicomputers the size of a chest freezer, costing as much as a light plane, arrived in the 1960s. They rapidly gave way to microcomputers the size of a typewriter, costing no more than a family car. Speeding up and shrinking continuously, they became cheap and ubiquitous. Now everybody has a smartphone as powerful as a 2004 supercomputer. And while most people use them to watch cat videos and send each other selfies, a small minority—mere millions of sorcerous software engineers, worldwide—use them for occult ends.

More brains in the world, and more computers, mean more magic: and the more magic there is, the easier the practice of magic becomes. It threatens us with an exponentially worsening explosion of magic, a sorcerous singularity. When it was first hypothesized in the 1970s, this possibility seemed so threatening that the security services gave it a code name (CASE NIGHTMARE GREEN) and considered it a worse threat than global climate change. Then the floodgates opened, and in the tumultuous wake of a major incursion that killed tens of thousands, the security services made a very explicit pact with a lesser demiurge. They pledged their support to a strong political leader who understands the nature of the crisis, and who has promised us that He will save the nation—for dessert, at least.

Long live Prime Minister Fabian Everyman!

Long may the Black Pharaoh reign!

Iä! Iä! N'yar Lat-Hotep!

H. P. Lovecraft (Racist, bigot, and author of numerous fictions of the occult that are as accurate a guide to the starry wisdom as the recipes for explosives in The Anarchist Cookbook) misspelled His name and libelously misconstrued His intentions. Egyptologists questioned his very existence. Nevertheless, N'yar Lat-Hotep is very real: an ancient being worshipped as a god for thousands of years who takes a whimsical and deadly interest in human affairs. For a period of centuries, perhaps millennia, He absented himself: but then, not so long ago in cosmic terms, He squeezed one of His pseudopodia through the walls of our world and installed Himself in a nameless, faceless human vessel. A cypher, a sorcerer overwhelmed, or one who made a pact with a force beyond his understanding: it makes no difference how it began, only how it ends.

Having obtained a toehold, He applied himself to the challenge of taking over a small and fractious landmass on the edge of Europe, a nation with an overinflated regard for itself, a fallen imperial hub not yet reconciled to its own loss of primacy. Its complacent rulers were easy prey for this canny and ancient predator. He took over the ruling party in the summer of 2015 and declared Himself Prime Minister for Life, to the unanimous acclaim of Parliament, the royal family—for the PM approves their civil-list payments—and the media—or at least those editors who value their lives. (Nobody bothered to ask the public their opinion: the Little People don't count.)

Since 2015, the New Management has made some changes.

His Dread Majesty is nothing if not a traditionalist, and also a stickler for the proper forms. By appointing His minions to the House of Lords He has brought the foremost occult practitioners of the land into His court—those who are willing to swear obeisance to Him, of course: there are certain followers of rival gods who are unwilling to bend their necks, and consequently run the risk of bills of attainder and execution warrants being laid against them. But there is a silver lining to His rule! He has very limited tolerance for corruption among those He entrusts with the business of government in His name. He prizes efficiency over humanity, consistency over mercy, permanence over progress. It is possible to thrive and grow wealthy in His service, but only as long as one's loyalty is above reproach and one strives tirelessly to build the Temple of the Black Pharaoh. The old oafish ways of bumbling inefficiency and furtive old-school handshakes passing envelopes stuffed with banknotes are banished forever! And the nation is healthier for all that.

It should be clear by now that worshippers of the Red Skull Cult, members of the Church of the Mute Poet, and devotees of mystery cults devoted to gods and monsters that claim to be His rivals are not, to put it mildly, likely to flourish under His Dark Majesty's eye. Which is why Eve's summons to pay court to the Prime Minister is such a big deal. As a high priest of Ppilimtec—the Mute Poet—Rupert was swimming against a riptide: but the Prime Minister is nothing if not strategically generous, and He has granted Eve an opportunity to kiss the ring, bend her neck, and distance herself from her missing-presumed-dead master.

At a price, of course.

To continue reading follow these links to the UK and US publishers' pages with links to retailers and ebook stores:

[British edition: available Thursday 18th] [US edition: available Tuesday 16th]

Looking forward to that.

"The year is 2017, and in a few months' time it will be the second anniversary of the arrival of the New Management."

I love the callback to Accelerando.

ROTFLMAO!

I'm very much looking forward to the book.

I will note that the novel takes off in a very different direction approximately 15,000 words later.

Johnny McTavish and Persephone Hazard!

So pleasant to meet old friends from The Laundry Files once again.

Not all that BASHFUL, but still quite INCENDIARY.

No footnote for triple parentheses? Those are opaque if you haven't already heard of them.

Charlie your blog is leaking!

No spoilers here I promise, although I am partway into the book . . . This excerpt includes the relevant ingredients. I feel silly not having consciously locked into this before, but I can now see the metanarrative to many or most of your books . . . Our protagonist is an ordinary person, usually a woman (or a geeky man full of naivete to make him vulnerable) comes into contact with a system of power in a situation where the alternatives are usually to seize the means they have to participate in and win in that power system or die (or face some other dehumanizing fate). They meet either a "partner in crime" or a mentor who reduces their likelihood of becoming food for the sharks they swim among. They are permanently changed or distorted by the experience, and may lose some of their humanity. And there are frequently even non-viewpoint characters who demonstrate the more horrifying aspects of this potential outcome. The protagonist suffers as the toxic juices of the metaphorical belly of the beast attempt to digest them, sometimes they also have the opportunity to become mentors, but I've never seen them escape the fate of becoming something entirely else than they were to begin with, frequently something that is no longer as human as they were to begin with (this awkward phraseology allows for androids). But it is more than a dungeon crawl full of corsets and murderbots and lawyers and bankers and tentacles and nuclear weapons and spies and scheming grandmothers and PRINCE II process diagrams . . . It is an attempt to pull off the velvet glove that covers up the bloody fist of power, in various forms. And under the New Management, that bloody fist is more visible to more people than it was before. Which changes the way this journey works a bit. And every time we go on this journey, we learn a little more. The books aren't didactic, but they are full of lessons. Find allies. Find the little comforts that hold body and soul together. Cling to humanity as long as you can, because you will be changed. And power is always polluted. It always has a price in blood. But these characters can't opt out of that system, cannot flee it. Some of them have to recognize their part in the sufferings of others, even their dependence on them, whether blood meals or undead guards or murdered bankers . . . . The trick is to be changed without losing humanity or losing touch with the horror of the cost of power or stopping lifting other folks up along with you to keep resisting, even though they too will have to go through that same painful transformation in order to keep a being that values life active in the power structure. And there is no final victory against that power structure possible. No boom wow the Empire has fallen, the witch is dead we won. Just the eternal struggle to rise up and pull the next generation along. And hold on to what matters as we do so. It is quite a realistic perspective.

I got further into the book and I'm at the Oh God, no.

Fellow readers you have been warned. Or tempted. Isn't that the same?

And it's available for download in the UK via Kobo today, not Thursday (because apparently Orbit either got the publication date wrong or managed to release it two days early to sync up with the US publisher)! Amazon.co.uk are still showing Thursday. So if you want an ebook you know where to go.

… That metanarrative honestly hadn't occurred to me although you're absolutely right: I'm probably too close to it to be consciously aware of what I'm doing but it seems to infuse about 80% of my fiction, doesn't it?

(I suspect it's my version of the humanist sensibility Terry Pratchett brought to bear in his fiction. Which is to say, I'm somewhat bleaker and more pessimistic about humanity's capacity for inhumanity ...)

It’s available on Kindle in the UK now. My pre-ordered copy turned up at midnight.

I don't have a UK kindle account so Amazon.co.uk won't show me that edition at all; they're still showing the 18th as the date for the hardcover.

I just saw my Kindle version from Amazon US. (At approximately 2023-05-16T12:00Z, to put it in ISO 8601-speak.)

My copy has landed too. Looking forward to it!

Noted in another thread - I just bought and d/l the ebook.

The marriage contract put me so much in mind of the latest lawsuit against Gullane.

Gullane? 56.035480, -2.829739!?

Typo: "Is the building is on fire?". It's in my actual copy as well.

Haven't read the excerpt because my copy is supposed to arrive any day now according to the bookstore! (I'm in the boonies and your last book took an additional two or three weeks to arrive, so we'll see.)

I hope it’s OK to point these out. Typos in the UK kindle edition (so far).

p64 - was in some wise unsatisfactory p99 - desert of figgy pudding p101 - Fiona’s hand was slipping (character’s name is Flora not Fiona)

"was in some wise" -- this is actually correct (but archaic) usage.

"desert of figgy pudding" -- yep, go look it up (traditional British pudding/dessert)

I'll cop to the typo'd character name (she got renamed during an edit pass)

I know about figgy pudding, but is it really found in a sandy waste? (I haven't got to that point in the book, so perhaps it was.)

What were the triple parentheses about?

Dammit, wasteland! (See, Torvald's Law of debugging also applies to closed-source works of fiction. You can never have enough proofreaders.)

The triple parentheses ((( name ))) are an anti-semitic tag used by neo-nazis to indicate that [name] is Jewish -- source. (Search engines typically ignore parentheses while indexing, making it really hard to search for posts or comments containing the notation.) I used it with deliberate ironic intent in Season of Skulls ("It was all a Russian disinformation scheme, a viral pandemic that induced delirious hallucinations, or a conspiracy of (((cosmopolitans)))") because of course if the New Management existed, you know the conspiracy theorists would be all over it -- including the neo-nazis.

Page 26: "The chain link came apart on the welded steam: ..."

I am not collecting typos at this time.

(I need to see if it's even possible to get them fixed at this point -- normally a book may be "fixed" when it's reflowed for a mass market paperback release, but that isn't happening at all with my Tor.com titles as they don't publish paperback editions. Orbit does, but Orbit source their typeset files from Tor.com ...)

Saw this over on Brin's blog, and thought it might be of interest here:

https://mastodon.me.uk/@garius/110339945582921150

Posting it here because it concerns the effects of honouring of a 600-year-old treaty in WWII, which reminded me a lot of Eve's legal problems (as described above) based on old laws in obscure jurisdictions.

Yeah, there are a lot of weird old laws still on the books (if you live in a nation old enough to have them). IIRC some parts of the UK's Treason Act still in force date back to the 1350s -- not the punishments, but subsequent Treason Acts simply tweaked the wording of the original so the bones are still there.

The only thing that's bothered me so far, by p 230 or so, is first Eve thinking that Macadam roads hadn't been invented yet (wikipedia says they were by 1820), then a mention that they're barely there, and then traveling on a Macadam road in the stagecoach.

And Charlie, you're an Evil Person. I d/l the epub to my Nook, then finally finished reading A Desolation Called Peace that had kept me "enthralled" so much that I only would read it for a few pages at a time, usually while waiting to see a hurse (every two weeks).

Then I started Season of Skulls yesterday afternoon, and I'm on p 245 of 324. How am I going to keep reading when I'm going to be finished soon?

As I recall, up until the 90s there was a loophole in the Treason laws that meant there were still, theoretically, three crimes carrying the death penalty.

1, Killing the King/Queen 2, Arson of Her/His Majesty's dockyards 3, Rape of a Princess of the blood royal. (ie Anne rather than Kate/Meghan/Diana)

I cannot recall if they got rid of them when the Blair administration got rid of anachronisms like the 1898 Perambulator Act - which was to force bikes onto the road but, also, inadvertently banned prams.

I could be wrong though.

At our house the one who gets the post in on the day the new book arrives gets to read it first. Looking forward to it.

"Then the floodgates opened, and in the tumultuous wake of a major incursion that killed tens of thousands, the security services made a very explicit pact with a lesser demiurge. They pledged their support to a strong political leader who understands the nature of the crisis, and who has promised us that He will save the nation—for dessert, at least."

I've been pondering if I should get into the New Management books, and I've concluded that it doesn't sound like my cup of tea, and this is why. Since Sir Terry was mentioned, there's a quote of his that I'm particularly fond of: "Sometimes it's better to light a flamethrower than curse the darkness." Instead of grabbing the flamethrower, the Laundry surrendered to the darkness. The whole premise of the setting leaves a bad taste in my mouth.

The former was largely true, but I think the third case was an urban myth. Anyway, I could find no evidence it was abolished that late.

The last is wrong. Prams were forbidden on pavements before 1898 according to statute law, and still are: Highway Act 1835, section 72. Yes, I know that no court would enforce it. I can't find the Act to which you refer, but it has certainly been repealed.

I suspect that section 78 of the HA 1835 (which is also still in force) is another codification of mediaeval law. I am pretty sure that the laws requiring the upkeep of private highways are even older.

I shall not post further on this.

Perhaps... but a) OGH is a good writer (note my "complaint", above), and b) living in the US, with the corrupt half of the SCOTUS, and after TFG, I don't really have any choice, other than to support Biden (who I consider a) too old, and b) too cautious/conservative). With that, I can root for Eve.

To my surprise, I find that /Season of Skulls/ reminds me quite a bit of /Babel: An Arcane History/, by R.F. Kuang.

I think that's vague enough not to count as a spoiler.

Yeah, there are a lot of weird old laws still on the books

I believe there are antisodomy laws that make homosexual sex a crime still on the books in some states of the USA. They are, of course, unconstitutional, and therefore not in effect. However, we have had a recent reminder that zombie laws can come back to life. Several states had very strict laws against abortion on the books. These were, until recently, unconstitutional because of Roe v Wade. But the recent reversal of Roe brought them back to life.

Looking forward to reading this. I hope Eve has a good strategy for getting out of the Bigge mess

he only thing that's bothered me so far, by p 230 or so, is first Eve thinking that

You hadn't noticed any sooner that Eve is not quite as well-informed about History as she thought?

I mean, the clues are all there -- her beliefs and the truth do not always match up (and in some cases are in conflict because this probably isn't a true reflection of the real 1816).

I was skeptical, in fact, that Eve would be able to easily communicate in English with folks in 1816. English in 1816 probably sounded very different from the way it does in the 21st century. Although I guess we can wiggle out of that by noting that Eve wasn't really transported to 1816 England, but to a dream of 1816 England.

Instead of grabbing the flamethrower, the Laundry surrendered to the darkness. The whole premise of the setting leaves a bad taste in my mouth.

Oversimplification.

First, the Laundry broke the Masquerade (or rather, failed to prevent an elven army destroying a large city in front of the news cameras).

Second, the government of the day responded by breaking the Laundry -- that is, by purging management and prepping it for outsourcing to Raymond Schiller's cult.

The Laundry survivors responded by activating an emergency plan (Continuity Operations) to take down the cultists, under cover of some murky precedents. This involved making a temporary deal with a Big Bad to see off the other Big Bad (who was implanting mind control parasites in the prime minister and cabinet).

The Big Bad saw off the cultists (good) but then installed itself in place of the decorticated Prime Minister (bad, very bad).

But that's okay, Continuity Operations have a Cunning Plan to crowbar the Big Bad out of 10 Downing Street.

(That's where the Laundry plot had gotten to as of "The Labyrinth Index".)

Still to come is another Laundry novel (not "A Conventional Boy" -- which is due out next year, and is a flashback to an earlier period), provisionally titled "The Regicide Report", on how Continuity Operations try to take on Nyarlathotep, and what the outcome was.

Clue: it's a lot messier than the outsider-summary in "Season of Skulls" (which positions the New Management as having won because of course anyone who made it that far was going to declare victory).

But really, the New Management books are about ordinary folks, not secret service agents, trying to live in a world gone mad. So kinda-sorta a metaphor for Brexit, among other things ...

English in 1816 probably sounded very different from the way it does in the 21st century.

My understanding based on current research is that English-English circa 1816 would be comprehensible, although the accents would be a bit odd.

Working class London accents of the period were very similar to modern Australian (because that's who the initial Australian colonists were drawn from -- British colonization began in 1788, so within 30 years of this novel).

The shift of the royal family towards a Germanic accent had already happened, and the upper crust would be aping it as usual. Pronounced RP wasn't universally understood and spoken as the default upper-status accent (because there was no audio broadcasting to spread it yet) but improvements in mobility meant that touring theatre troupes and circuses were a thing, which in turn implies that folks who could afford such entertainments could also understand such accents/dialects as the performers spoke -- and they had an incentive to be as near universally understood as possible.

Go back 200 years earlier and it would be a very different matter, although it's believed that current American accents reflect those of older Modern English (circa 1600-1750).

Go back to 1416 instead of 1816 and you'd need an interpreter, although the nobs wouldn't be talking English at all (it'd all be Norman French or Church Latin).

Speaking of written English rather than spoken, there was obviously a major shift between 1600 and 1750-ish. Shakespeare and the KJV are sometimes problematic for modern readers, but mid-C18 texts are perfectly comprehensible if a bit quaint. Probably corresponds to the shift from spoken Early Modern English to Modern English.

Most older German laws were superseded by German BGB in 1900, but in certain circumstances older local law prevails.

So according to German Wikipedia, Jutlandic law still partially applies in parts of Schleswig-Holstein and was quoted in court decisions concerning property rights till 2000; the original version is from 1241, the version used was somewhat later (16th century), but since the law stayed basically the same it doesn't matter that much.

As for SoS, Book arrived today, only positive effect of the whole coronation spectacle was Thalia gave me a 20% price reduction on forein-language titles. Err, yes, I'm a cheapskate. (Some books by Mr. Naish of TetZoo fame stimm need to arrive.)

As for Eve's secessional ambitions, another idea would be using the Petrine privilege if Rupert wasn't baptized; Pauline privilege likely doesn't apply, since Eve was baptized before the, err, "marriage".

Yeah, there are a lot of weird old laws still on the books (if you live in a nation old enough to have them)...

And for those of us in the United States, we have bonkers new laws sneaking in. Anything under a century old is "new," right?

Relevant to the topic at hand, last night I was killing time with some Legal Eagle videos and happened on to "Rights You Didn't Know You Had (and Probably Don't Want)." It talks about proxy marriages, which are a thing in a surprising number of US states - although all the participants are expected to know about the wedding. The bizarre outlier is Montana, which allows both bride and groom to send stand-ins and will honor a marriage ceremony in which none of the participants actually participated. (And if at least one of them is on active duty with the US military, neither of them have to have ever lived in Montana!) I can only assume this made sense to someone.

On treason ...

The Treason Act 1814 sets the penalty for treason. It originally ended "such person shall be hanged by the neck until such person be dead" but now ends "such person shall be liable to imprisonment for life" - this wording was substituted by the Crime and Disorder Act 1998 s.36, which got rid of the last instances of the death penalty (memory says to bring us into line with the European Convention on Human Rights).

The Acts modified were the Treason Act (Ireland) 1537, Crown of Ireland Act 1542, Act of Supremacy (Ireland) 1560, Treason Act 1702, Treason Act (Ireland) 1703, Treason Act 1814, and Piracy Act 1837.

The offences involved are described as: * practising any harm etc. to, or slandering, the King [of Ireland], Queen or heirs apparent * occasioning disturbance etc. to the crown of Ireland * defending foreign authority [death penalty on third conviction] * endeavouring to deprive or hinder the succession to the crown * piracy with intent to murder

There's nothing specific about arson in dockyards (though I'd heard that one before) or raping anyone, unless I missed it in the long block of 16th century prose. But slandering the King of Ireland is a new one to me.

The Treason Act 1842 s.2, still in force, says "If any person shall wilfully discharge or attempt to discharge, or point, aim, or present at or near to the person of the Queen, any gun, pistol, or any other description of fire-arms or of other arms whatsoever ..." with a penalty of 7 years "transported beyond the seas" (though other legislation has said that this is to be interpreted as up to 7 years in prison). I can remember someone being charged with it back in the 80s, with the papers making a big fuss about the treason charge.

I don't know exactly when it landed for me, probably the 16th. I finished the Tallis book I was reading, looked in my Kindle library and there it was. I'm 35% in as of now. It's good.

Your taste is your taste of course, but I think you are comparing apples with oranges; Sir Pterry was writing adventure fantasy with a humanist subtext, while OGH is writing horror with a humanist subtext.

I read the Laundry books as about the horror of trying to hold on to your humanity while looking for the least bad option, and the New Management books as about the horror of surviving into a dehumanising present, both with a heavy layer of satire comparing that present to the UK in the real world. In your metaphor, the Laundry characters grabbed the flamethrower and it cooked them as well as what they were aiming at, and now Imp etc. are trying to stay warm around the embers.

If I were to write something like NM it might be a post-climate-collapse story with the relics of disaster capitalism being the only remaining infrastructure that's livable and able to support a population.

My understanding is that people familiar with at least some of the accents / dialects still spoken in the 1950s would be able to understand the relevant English of 1616 (i.e. it varied a LOT with area and class) with some initial difficulty. I could once understand one or two, but couldn't now. There has been a massive shift since the 1950s, and most of the smaller dialects have disappeared. I can witness that Londoners couldn't understand even Wiltshire farm-workers in the 1960s.

As you say, 1416 is another matter entirely.

I can remember someone being charged with it back in the 80s, with the papers making a big fuss about the treason charge

And then there's this: Windsor Castle intruder pleads guilty to threatening to kill Her late Majesty Queen Elizabeth II -- guilty verdict handed down on 3 February 2023, I haven't seen any sign of sentencing yet. Per the CPS, "The court ordered medical reports be prepared before sentence" (because there were more than a few indications of psychiatric issues).

If I recall correctly, the penalty for arson was repealed somewhat earlier, but the story got attached to the Crime and Disorder Act 1998. But my memory may well be wrong.

I can witness that Londoners couldn't understand even Wiltshire farm-workers in the 1960s.

I know for a fact that southerners, including Londoners, couldn't understand folks from Huddersfield as recently as the late 1980s.

Source: I had to act as an interpreter between fellow students during my first degree.

Remember that the time from Shakespeare to Fielding is essentially the same as from Fielding to Tolkein, so you would expect twice as much difference! Furthermore, Shakespeare wrote in the common English of the era, not the more intellectual form used by some other writers.

I can witness that Londoners couldn't understand even Wiltshire farm-workers in the 1960s.

I have an English friend who lived a long time in Finland. At some point here some Finn asked them if it is hard to understand the Finnish accents. They answered that, no, Finnish accents are easy, the most difficult to understand accent they've encountered have been some in the middle of England.

After that I basically stopped caring about my accent. The point usually is to get understood and that's enough.

For me, the most difficult accents to understand have been from Dublin and Glasgow, but I think it's mostly because I haven't been exposed to them that much. If I was to spend time in either of the places, I think I'd begin to understand the local accent quite fast.

This reminds me a bit of the computer game 'Disco Elysium'. It's an adventure game set in a kind of dieselpunkish fantasy world, and there are various languages and accents there. It's an Estonian game but made principally in English, and it was fun playing the game and upon hearing one character's voice I could immediately say 'the voice actor is Finnish'. She was.

That is something that annoys me about most time-travelling fiction. Go back to the 18th century in Loamshire, and you could probably understand Lord Landowner and the Reverend Mr Prelate, but be defeated by Samuel Innkeeper, and would be unable to tell even that Peter Plowman was speaking English.

It does get worse. I have German friends who speak "good English" but were utterly mystified on a visit to Aberdeenshire until they mentioned it to me years later and my response was "You speak good English and were listening in English. They were speaking the guid Doric leed, an' yon's a new tongue tae ye quine". I then translated the second sentence. Point?

For me, the most difficult accents to understand have been from Dublin and Glasgow, but I think it's mostly because I haven't been exposed to them that much.

Scots is halfway to being a different language -- a lot of the grammatical constructs reflect post-Roman Scotland having been largely a Viking colony prior to 1000CE, while England got a lot of Angles and Saxons. There's also the legacy of Gaelic, which is still spoken by a minority in outlying areas (and note that Scottish Gaelic is not the same language as Irish Gaelic).

Ireland in turn ... there was a lot of invading back and forth between Scotland and Ireland after the picts: the most recent wave in Ireland were the Scottish settlers in the 17th century who the Ulster protestants are descended from, but the source of those immigrants were descended from Irish invaders in western Scotland from a few centuries earlier.

But anyway, as I understand it regional Scots and southern English dialects are probably as mutually comprehensible as Norwegian and Swedish, although "Pronounced RP" (BBC English) is understood pretty much everywhere, even in the USA.

Thanks to everyone who confirmed that 2 out of 3 of the laws I remembered as carrying the death penalty were urban myth. Sometimes myth can be so much more satisfying than reality.

Amused to see OGH mentioning that his latest book involves normal people trying to cope in a world gone mad. I've just read Moving Pictures by P'Terry again, and hope to read the new tome later in the week and find out where the 1,000 elephants will fit in.

On the subject of accents I can believe Londoners struggling with Wiltshire, but how did the Wilts folk cope with a London north, east or south accent? When I was young you could tell those 3 apart easily, now everyone sounds like they come from Essex.

My favourite fact about Glasgow English is that the comedy series "Rab C Nesbitt", set in Glasgow and with characters speaking in a fairly strong Glasgow accent, was originally shown on the BBC with subtitles as if it was a foreign-language programme. This was 1988.

Re translation, I was brought up in Lancashire but spent plenty of time in the Midlands, as well as having the whole "My Fair Lady" experience for enunciation when I did singing lessons, so my accent is generically northern without being too specific. One of my coworkers in the 00s was from the Lancashire valleys, and had a very strong accent. Much of the time, I did literally have to translate for him to the rest of the team (random mix of English people with one Scot and one Indian, based in Cambridge). This was very much EC's "Peter Plowman" problem.

When I was working in London in early 1993 (delivering benefits to the unemployed etc. in the office nearest the train stations with the lines going North) I was regularly asked to come to reception in order to speak to people who had just arrived from Scotland as the southern staff couldn't understand them. Admittedly sometimes that was because the Scots were putting it on a bit in an attempt to intimidate the staff into being lenient regarding entitlement requirements. On the other hand, I was inspecting an office up near Aberdeen a few years ago with a colleague who also grew up in the North West of England. Some of the staff went full Doric while talkiong to each other, assuming that we couldn't understand what they were saying. Unfortunately for them I could....

Until relatively recently all broadcast media were delivered in RP English, so everyone was used to hearing something quite close to a Southern accent. Non London dialects were not commonly broadcast so Londoners were not used to hearing them and struggled.

Go back to 1416 instead of 1816 and you'd need an interpreter, although the nobs wouldn't be talking English at all (it'd all be Norman French or Church Latin).

Here's an example of the Middle English of that time: Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, written in the late 14th century but surviving in a single MS copy made in the early 15th.

I can, with considerable effort, read most lines of this and arrive at some notion of what they're about. Many, however, leave me completely baffled (or would, did not translations into Modern English exist). God only knows how it sounded.

To riff on the late Stephen Jay Gould, languages seem to evolve via punctuated equilibrium, rather than continuous gradual change.

To riff on the late Stephen Jay Gould, languages seem to evolve via punctuated equilibrium, rather than continuous gradual change

I thought the same at one point. When I did Hot Earth Dreams, I decided to check, and it turns out that's sort of not the case.

The book I read was McWhorter's The Power of Babel: A Natural History of Language. It's from 2003 and not available as an ebook, but there are a bunch of used copies floating around for cheap and it might be available in libraries outside the US.

Anyway, yes, pidgin languages arise fast, because they're based on the need for people who don't share a language to communicate. Creoles (fully formed languages built on pidgins) take a generation or two to form: basically the children of a group of people forced to live communicating in pidgin build it out to a fully featured language.

So that part is like punctuated equilibrium.

The part that's not is that oral languages also tend to change really fast. Writing tethers a language to a written corpus and seems to slow down the rate of change, especially with the printing press and widespread literacy. This is why Shakespeare's printed English is fairly comprehensible, Chaucer's written English of a few centuries earlier is a lot less comprehensible, and Beowulf of a few centuries before that is basically a foreign language. What you're seeing is a changing language slowing down as more people need to be able to read it. Oral-only languages mutate as fast as slang does, and for much the same reason: people of different generations simply emphasize the words they prefer, drop the ones they don't, coin new terms, play with language, keep in-jokes and wordplay, and so forth.

Language can also change fast due to politics. North Korean and South Korean are examples of this. South Korean contains a LOT of words imported from Japanese and English, due to its colonial history, while North Korean was deliberately purged or foreign elements. More generally, languages can both include some people and exclude others (cf technical jargons), and that always has an element of politics in it.

Finally, the weird, painful thing for an American like me to realize is that globally, throughout history, most people have been multilingual. Monolingualists, like me, have generally been a disadvantaged minority.

Anyway, the book is fun, and it goes into a lot of detail about the crazy/genius/mind-boggling things people have done with oral communication. I recommend it.

To riff on the late Stephen Jay Gould, languages seem to evolve via punctuated equilibrium, rather than continuous gradual change.

I would have supposed that we are now in a period of equilibrium, with little change taking place. Widespread literacy and broadcasting would seem to freeze the language.

Yet, for no obvious reason, a vowel shift took off within a part of the USA. The resulting dialect is called Inland Northern American English. I moved from New England to Western New York in 1969, and it was immediately obvious to me that vowels were pronounced differently. In New England "thought" is pronounced "thawt". In regions where Inland Northern American English previals, it is sounds like "thaht".

Now, this is quite a mild language change. There's no loss of mutual intelligibility, and the words of this new dialect are for the most part the words of ordinary NA English, albeit pronounced differently. Still, it shows that language can evolve sympatrically without obvious causative pressure.

I've read that US radio networks hired midwesterners for voice talent preferentially because their accents were comprehensible to more listeners, such as Walter Cronkite* of CBS.

*From Saint Joseph, MO.

"Transported beyond the seas"? These days, the only way I can read that is, of course, offplanet.

What do I have to do to get sent to the Moon?

"Finally, the weird, painful thing for an American like me to realize is that globally, throughout history, most people have been multilingual."

Language competence is often broken down into four components: reading, writing, listening and speaking. Throughout history most people have been illiterate, but today you can be usefully literate in a language and next to hopeless when it comes to oral communication. (I can read Russian and Spanish newspapers reasonably well, but have to depend on the patience and good will of others if I try to speak those languages.)

What it sounded like? May I strongly recommend a translation, using the same alliterative verse patterns, by this obscure Oxford scholar... JRR Tolkien. It's wonderful, and you get to find you enjoy alliterative verse.

Oh, and I have absolutely zero problem assuming Eve can make herself understood: she's on the dream roads. They all speak the same version of English that she does, or vice versa.

The running joke Clarkson's Farm is that one of the older contractors speaks what sounds like gibberish (there are some indications that this is an act for the show...).

If you watch the movie RRR (I think still on Netflix), you can watch it with English sub-titles, which don't always say the same thing as what the characters are saying (in English). They try to translate some Indian idioms, it gets a bit weird at times...

Beowulf of a few centuries before that is basically a foreign language

To the English-speaker, yes. To a Frisian-speaker, I believe it's still perfectly intelligible after all these centuries.

I once read a book about the evolution of English which worked backwards in 200 year jumps. If I'm remembering correctly, in one of those jumps (perhaps the 14th century) there were four separate and mutually-unintelligible versions of English. One reason for our odd spellings (there are others) is that Caxton spoke London English and so spelled words on that basis, while the version that won out was Midlands English, with different pronunciations.

"To a Frisian-speaker, I believe it's still perfectly intelligible after all these centuries."

You caused me to check the Wikipedia page on Frisian, which contains this:

I have no idea if that's actually the case, but would like to believe that it is.

Four? I read, many years ago, that before WWII (or was it WWI?) there were 246 or so mutually-incomprehensible dialects in the UK.

In the 1960s, I was given a lift in the back of a van driven by two Frisian farmers - I could ALMOST understand their conversation!

Go back 200 years earlier and it would be a very different matter, although it's believed that current American accents reflect those of older Modern English (circa 1600-1750).

Which ones? New England, especially around Boston are very different from the "hard south' (Georgia to Mississippi) which is different from Applilachia. Once you get out of those areas it settles down a bit to be mostly comprehensible. But Detroit and Pittsburgh can be very distinctive. Or were.

Louisiana is in another world with the French / English / Patois mix.

There's also the other thing; Hiberno-English speakers tend to speak faster than other English speakers. No idea why, but it seems to be true. Presumably the crowds of ESL students here decided they wanted to do it in hard mode. :-P

Go back to the 18th century in Loamshire, and you could probably understand Lord Landowner and the Reverend Mr Prelate, but be defeated by Samuel Innkeeper, and would be unable to tell even that Peter Plowman was speaking English.

At a local get together at a pub/sport bar not too long ago in North Carolina. One person was from England and it was somewhat obvious from his accent. Then as a joke he started talking in the dialect/accent he grew up with in a more rural setting. Not even all the UK folks could understand him. I was totally lost.

To a Frisian-speaker, I believe it's still perfectly intelligible after all these centuries." [...] I have no idea if that's actually the case, but would like to believe that it is.

Back in my Demon Internet days (OGH will remember those), we had an office in Amsterdam. The staff there insisted this was true.

Four? I read, many years ago, that before WWII (or was it WWI?) there were 246 or so mutually-incomprehensible dialects in the UK.

I'm skeptical. Distinct dialects, yes, but the fact that some words differ and there's some changes in pronunciation does not make them mutually-incomprehensible. I mean Geordie is not Mackem, and Henry Higgins could probably have distinguished a Sanddancer from either of those, but they can all understand each other.

I've probably got my own dialect - Cockney father, grew up in Sarfend, went to school in rural Essex, lived over 40 years in Cambridgeshire, and married to a Sanddancer, so I've got a mix of pronunciation and word choice. But most people seem to understand me (Americans excepted).

I've read that US radio networks hired midwesterners for voice talent preferentially because their accents were comprehensible to more listeners, such as Walter Cronkite* of CBS.

There is a thing called TV English in the US which is likely a midwestern accent but more subdued. The point was to take as much localization out as possible. Especially for nation wide shows and ads.

Which is likely why I don't hear nearly as much southern drawls when in the south as I did in the 60s and 70s.