There's a lot of concern about health care on both sides of the pond these days, with the recent worries about the National Health Service, and regime change in America bent on rolling back the benefits his predecessor put in place. In fact, one editorial to my regional newspaper had a headline that feared a return to the Dark Ages.

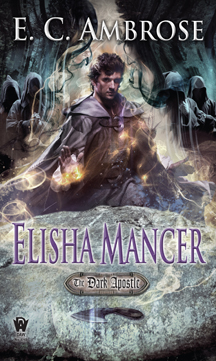

I write the Dark Apostle series for DAW books, dark historical fantasy about medieval surgery, which continues today with new release, Elisha Mancer. As a researcher into the history of medicine, all I could think was, they don't know much about the Dark Ages, do they? So here, for those who would like to make their comparisons more apt, is a basic primer to medical care through the 14th century.

1. Medical practitioners were highly educated professionals.

Aside from those who needed the midwife (a specialist even then), most patients sought one of three levels of care, depending, then as now, on their location and their level of income (about which, more later).

Physicians were considered minor clergy. They traveled to study at prestigious schools like Paris, Bologna and Salerno, where they learned from famous practitioners and memorized or transcribed important texts--often texts that were a thousand years out of date, such as the works of first century Roman physician, Galen, who passed along the theory of the four humors. Physicians generally worked with members of nobility, attached to the court of one monarch or cardinal or another, dispensing invaluable advice, such as the pope who died of eating too many ground emeralds on the advice of his doctor. Well, that advice was valuable to the gem merchant, anyhow.

Surgeons might also attend medical school, though their training tended to the practical. They often apprenticed to a master surgeon for seven years to develop their craft. Considered by the physicians as mere craftsmen, surgeons performed a variety of operations, from removing injured or diseased extremities to treating cataracts and the complaints of the knightly class, like anal fistula, a problem developing from too long in the saddle. They wrote and exchanged treatises on these specialized surgeries, and often maintained lively correspondence to share medical advances with their fellows.

As for barbers like Elisha, the protagonist of my books, they were considered the lowest form of practitioner. Like the surgeons, barbers apprenticed to learn their trade, but were much more plentiful, and thus accessible to a wide range of patients. Treating wounds, cutting hair, and bleeding patients on the order of the physician or surgeon, not to mention the occasional amputation or simple surgery.

2. Treatment depended on your finances.

Not everyone can afford to retain their own personal physician to prescribe emeralds or prepare a bath of mother's milk. Fortunately, many cities had charity hospitals where the poor could seek treatment from physicians and herbalists retained by donation. Alas, these institutions were often (then, as now) the source of as many sicknesses as they hoped to cure, and only the desperate sought them out, to be tended by nuns in large wards where they lay three to a bed and hoped for the best.

London is home to St. Bartholomew's the Great--the church, and its accompanying hospital, founded in 1122 by Rahere, King Henry's retired royal fool. Here in America, we have St. Jude's, founded by comedic actor Danny Thomas.

Tradesmen had another avenue to pay for their treatment. Many merchant and craftsmen's guilds offered group insurance to their members, covering medical care, or funeral expenses as the need arose. So the Middle Ages are perhaps the origin of what in America we term the dreaded "socialized medicine," in which people band together to care for each other. Not such a novel concept after all.

3. A humorous notion?

The four humors--black bile, yellow bile, blood, and phlegm--were said to travel through the body and to be accessible at certain points. Many illnesses were thought to be related to an imbalance of the humors, which could be cured by bleeding the patient to remove some of that particular humor being carried in the blood. Elaborate charts showed where to cut and during what season (because the humors could be more or less aroused due to the season, especially given a person's astrological sign). Although bleeding as a treatment has, thankfully, fallen by the wayside, the idea of the humors remains, whenever someone is described as Sanguine (too much blood), Bilious (too much bile), or Phlegmatic.

4. Alternative Medicine

Many people simply relied on ancient cures--charms, prayers and superstitions--to defend themselves from disease. Some of these cures depended on ideas of sympathetic magic--like spreading a special ointment on the weapon that caused a wound in the impression that this would cure the wound itself, or that the shape of a particular plant resembles the body part it is intended to treat. Others depended on effective herbs available locally or grown in one's own backyard. Willowbark, which contains Salicylic Acid, AKA Aspirin, was known to be good for a variety of aches and pains. In the absence of access to medical care, people made due with whatever they had on hand, and the advice of friends and neighbors. Fortunately, about half of all medical concerns will resolve themselves in relatively short order: either with the patient's unaided recovery, or with their death.

5. Honey, maggots and leeches

And of course, some of those old cures have returned to us today. Maggots, often used during the Middle Ages to debride wounds of rotting flesh, are being used once more for the same purpose--but they are now grown in special laboratories, and distributed in a dressing which prevents them from roaming about unsupervised, a great relief to the squeamish. Leeches have a unique enzyme for maintaining blood flow, and are handy for certain kinds of surgical procedures, especially the re-attachment of limbs and skin grafting. As for honey, it has antiseptic properties which make it handy for minor injuries and burns. But please, don't attempt any of this at home, especially this next one.

6. Like you need a hole in the head

Finally, let me say a word about the most infamous of medieval operations, trepanation. Some will tell you that trepanation was performed to "let out demons" or other such foolishness. In fact, if you look at the surgical texts and records of the day, this operation was advised to relieve pressure on the brain from an injury (often received in battle), and survival rates, based on bone re-growth shown in skulls from cemeteries, were as high as 90% (with the caveat that a number of potential patients likely died before they ever reached the surgeon's care). The source for this slander against the medieval surgeon comes from a sociologist who saw a skull with such a piercing at an archaeological site, and was asked to speculate on why such an operation might be performed. From what we can tell, like many outsiders commenting on the treatments of others, he had no idea what he was talking about.

So perhaps the letter-writer has made their mistake, not in thinking we are returning to an earlier era of medical treatment, but in failing to recognize that the medicine of the Middle Ages had ever left us.

If you'd like to know more about the Dark Apostle series of fantasy novels about medieval surgery including sample chapters, historical research and some nifty extras, like a scroll-over image describing the medical tools on the cover of Elisha Barber, visit www.TheDarkApostle.com/books

E. C. Ambrose's blog about the intersections between fantasy and history or follow me on Twitter or Facebook

If you haven't started reading The Dark Apostle, pick up volume one, Elisha Barber, wherever books are sold, includingIndiebound, Barnes & Noble, or Amazon

The fourth volume, Elisha Mancer, from DAW books, is now available!

What about apothecaries? During a period of British history I know a bit more about, the eighteenth century, as I understand the matter, apothecaries not only compounded drugs, but decided what drugs to recommend for different illnesses, which I suppose must have involved some skill in identifying the illnesses; as a result, they were a third stratum of practitioners, socially lower than physicians or surgeons. Was that not the case in the Middle Ages? If not, there go the herbalists of a lot of medievalist fantasy I've read. . . .

Yes, the medieval period was a bit different. There were herbalists of various sorts, more or less educated, and a mass of half digested popular wisdom circulated too, some accurate some not, and some traceable back to the older scholarly medicinal texts, but often changed a bit through the transmission. As far as I can recall, apothecaries were indeed used to make up the medicines, but it makes sense that they would take on more and more of the prescribing role over the centuries.

To say more i'd have to look up the books.

Apothecaries begin to emerge in England around the time of my work (14th century) and there's one mentioned by Geoffrey Chaucer in the Canterbury Tales--but they become much more prevalent in the 16th century (their guild company in London was founded in 1617). It would be interesting to study that expansion of the trade--why then?

In any event, they were gathering, compounding and supplying medicines, often at the behest of the physicians. There is a fantastic museum devoted to the apothecary at Heidelberg Castle in Germany.

Thanks for reading.

Great stuff, thanks very much for that!

What's the real dope on what medicines and procedures they had that actually worked? For instance, you mention willow bark, but how well off were they for other things that did actually contain some relevant active principle?

There's also all the legal fights between the surgeons and barbers in London over exactly who was allowed to do what work.

Are you thinking in terms of prescribing remedies? During my period, most of the compounds were notoriously based on their relation to the humors, so if a person's humoral balance was considered to be hot and moist, they would be given remedies that were cool and dry. This is one case where the wikipedia article on Humorism does a very nice job of charting out the relationships between the humors and their properties.

Diagnosis was often made by examination of the urine, and it was important to note the patient's astrological sign and the season of the year. So a Scorpio might be given one medication for a particular set of symptoms, while a Cancer would be given a different compound (and either one of them might have a different prescription entirely in the spring versus the winter).

One of the reasons I focused more on surgical practice in my writing was that the physicians (the internal medicine guys) tended to be obsessive about things with no practical basis whatsoever, so my barber protagonist allows me to make fun of them.

Thanks for reading!

Yes! The in-fighting between classes of practitioners at the time was incredible. There was a lot of overlap in simple procedures between the surgeons and the barbers, which ended with the surgeons getting frustrated because the barbers usually charged less. Hence, the surgeons' repeated attempts to regulate who did what, and to paste the barbers with the reputation of being hacks and butchers because they generally had less education.

This is one of the reasons people like Guy de Chauliac (the surgeon who became Pope Clement VI's personal doctor) and Ambroise Pare (16th century barber-surgeon to the king of France) are so interesting. They seem to have been so skilled and trusted that they rose to very high service, in spite of the prevailing climate.

"Wonderful little, when all is said, Wonderful little our fathers knew. Half their remedies cured you dead-- Most of their teaching was quite untrue--" — Kipling, "Our Fathers of Old"

that's perfect--thanks for sharing!

It's easy to make fun of Galen and how long he was read and taken seriously. But I wonder, if punching a whole in someones head had a 90% survival rate, clearly there must have been some sort of evidence based approach in a craftsman's sense? "Evidently, the pick is too large or the hammer too heavy, we'll try this differently with the the next one. Undertaker!"

Rahere, King Henry's retired royal fool. READ "The Tree of Justice" - Kipling QUOTE: More a priest than a Fool & more of a Wizard thein either" ENDQUOTE Barts' is still going - I've been treated there ....

Sympathetic "magic" & the Doctrine of Signatures. Problem ... inevitably in one or two cases, it would work, even when it didn't most of the time. The cases I know of where it di work are: Ranununculus ficaria & Pulmonaria officinalis So there.

I frequently find myself wishing for a modernernised form of trepanning that would allow a sort of psychological tap to be installed. Drain out most of the depression/anger/abject terror that's preventing me from functioning on any given day... (Taking away enough to enable me to fight the fascists, while leaving enough to ensure that I actually do.)

Worth reading the Christoval Alvarez books by Anne Swinfen (http://annswinfen.com/) the eponymous character of which is a physician in late Elizabethan England. The books provide some history about the various hospitals in London, the state of healthcare at the time (not as bad as one might think) and the medicines and treatments available (I can't find any information about some of them - Coventry Water for example, which I assume is an antiseptic). Add to that some interesting history.

Apologies - Ann (not Anne) Swinfen

I was wondering the same thing, sort of. Why would people keep pushing the humor theory for so long? Things must have gone right from time to time, and these would have been ascribed to the correctness of the humour-based treatment. Is this an example of confirmation bias? Do educators use this example to teach about evidence-based treatments?

What did physicians conclude when a humour-based treatment failed? Demons, withcraft? God's will? That could 'account' for a large number of the treatment failures, bolstering support for the humour theory.

"Established Authority" Was more important & better-regarded than Evidence. Effectively that ( along with religious dogma, of course, which is also "established authority" ) was what got Galilei condemned & Bruno burnt.

Fun fact: even in the modern era, until the widespread adoption of CT scanning in the 1970s/80s, the lucky surgeon on duty was flying about as blind as the Aztecs or Egyptians when it came to trepanning. If you had a trauma victim with a suspected epidural bleed, you started drilling first and asked questions later. And if you got nothing, you kept drilling holes around the head until you hit a gusher. It's really no wonder that trepanning is one of the oldest (and most successful) surgical procedures we have. It's a no-brainer.

The first person in history to attempt it had some balls, though. And the first person in history to attempt it and succeed deserves even more kudos.

this is a great idea--let me know when you've got the kinks worked out!

The use of trepanation for compressed skull fractures has been going on for a very long time (as commenter Dromeaopunk observes)--much of the evidence we have is from ancient Peru, again, including a large percentage of skulls that show bone healing after the surgery. I think you're essentially right about practical experience. I imagine the early battlefield conversations going something like this:

This guy got his head bashed in. He's still alive, but not really functional.

Well, the bone isn't supposed to be concave like that. If we could just pop the dent out, he'd be fine.

::fiddling about with pointed things to pry the bits of skull back into alignment::

There we go!

And the operation gets more sophisticated over time, with improvements in tools and methodology.

Now I have to find a neurosurgeon and try convince them their field has shared origins with panelbeating. :-P

One of my historical inspirations, Ambroise Pare, used to say "I stitched him up, and God healed him." So yes, there is often a sense when you read the documents of the time, that God's hand is involved in medicine. The treatment is effective when God wills it so.

Given the number of of medical concerns that will work themselves out without any intervention, you could imagine if a patient received a treatment based on their humoral imbalance, and got better (through no fault of the treatment) the doctors would claim victory, with God's assistance. And if it failed, well, the patient was now in a better place. Leaving little incentive to change methods or explore the root causes of the deaths.

However, there are always individuals who observe cause and effect a little more closely. Pare is also notorious for proving to the king that Bezoar stone, (a mass removed from the intestine) which was said to counteract any poison, was a fraud. A man who was condemned to die volunteered to aid the proof by being poisoned instead of hanged. Pare then applied the Bezoar stone, which had no effect on the poison. The patient/victim/criminal died a long, agonizing death, but the king was convinced.

'Trepanning is... a no-brainer'.

I see what you did there.

"The source for this slander against the medieval surgeon comes from a sociologist who saw a skull with such a piercing at an archaeological site, and was asked to speculate on why such an operation might be performed. From what we can tell, like many outsiders commenting on the treatments of others, he had no idea what he was talking about."

Could I get a cite for this?

A google for

trepanning demons "sociologist"

turned up nothing.

Update, the statement in the post appears to be incorrect. Apparently a french Neurologist from the 1800's asked about neolithic remains was where the supposition came from and wasn't entirely unreasonable since many mental problems routinely got attributed to demons and spirits in various still extant cultures and many interventions claim to be "removing" them.

There's a time-travel Japanese manga series called "Jin" which has a modern surgeon sent back in time to 1860s Japan. He has to face an entrenched medical establishment that is adapting to Western medical knowledge flooding into the country after the Meiji Restoration while trying to introduce his own advanced medical knowledge -- starting a penicillin factory is only one part of the plot.

Surprisingly the high-ranking practitioners who control the medical schools and major hospitals are not totally averse to his interference in their business but it does not go totally smoothly for him.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jin_%28manga%29

We know that a century in the future, novelists will write about medicine of our day, making sure to mention stuff which we think of as normal and which future readers will think of the same way as we think of bleeding.

We just don't know which medical practices those are.

I have some large chunks of titanium in me now due to a severe accident, and discussing this situation with a number of medical friends of mine convinces me that a large part of modern surgery is effectively just carpentry with expensive tools and very expensive nails.

Honestly, an intermedullary nail going in mostly just involves a big hammer and a fair bit of enthusiasm, and then the drills come out to line the crossbolts up properly.

Herbal medicine has never gone away and is still in such widespread use that respected western-med national research bodies study them, e.g., German Commission E. Probably the best example of the relevance of studying traditional/herbal medicine is this 2015 Nobel laureate's work:

Wikipedia:

'Tu Youyou ... a Chinese pharmaceutical chemist and educator ... Her discovery of artemisinin and its treatment of malaria is regarded as a significant breakthrough of tropical medicine in the 20th century and health improvement for people of tropical developing countries in South Asia, Africa, and South America. For her work, Tu received the 2011 Lasker Award in clinical medicine and the 2015 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine jointly with William C. Campbell and Satoshi Ōmura. ...'

Artemesia has been used for malaria and worm infestations for thousands of years in many parts of the world so this 'discovery' is actually the modernization of ancient knowledge. Quite a lot of contemporary pharma research involves sending various types of PhDs into jungles/remote areas to track down isolated peoples in order to study their medical lore re: local plants and animals.

Question for Guest:

The spice trade that features throughout most recorded western history: what proportion was food seasoning vs. medicinal vs. good for both?

The problem with "herbal" medicine is not its effectiveness or reality, which has never been seriously doubted, but that of dosage. Because a plant contains an effective chemical for $Problem is only the easy bit. Because the soil the plant is growing in, how healthy the plants are, how much sunshine it got this year (etc etc) can enormously affect the quantity of $Useful_Chemical that said plant contains. Whereas, if you can synthesise the chemical, then you know how much you have got.

A particularly delicate problem if the effective dose, is say 75% of the fatal dose! Think particularly of foxglove : digitalin or deadly nightshade : belladonna as examples. Other plants that even I know of to have some useful medicinal properties ( often as well as a culinary use! ) include, apart from those above: St John's Wort, Lesser Celandine, Thyme ( & almost all the other culinary Labiates ) Garlic, Bee Balm, Hyssop, Tarragon & Mugwort, and, of course Opium poppy. That's all I can remember, off the top of my head for now (!)

Good points ...

This is made even more complicated by how many subtypes of the active compound exist, their relative proportions, etc. So, while I respect herbal medicine, I'm leery of self-medicating with it.

"The spice trade that features throughout most recorded western history: what proportion was food seasoning vs. medicinal vs. good for both?" SFreader at 30.

You might find "The Roman Empire and Indian Ocean: The Ancient world Economy & the Kingdoms of Africa, Arabia & India" by Raoul McLaughlin interesting. He has a whole chapter (#3) devoted to incense and spices and how they were interchangeably used as fragrances, flavorings and medicines in the early Roman Empire period.

The ancient Greeks used trepanning. There is IIRC a historical book series about a Greek physician who performs such an operation. There have been archeological findings of Greek skulls with healed trepanning.

Will have to read your books because I'm interested in medicine generally as well as its history. Have a few questions about middle ages medicine:

How did surgery/medicine vary by region ... was Poland spared from one of the largest Black Death epidemics because they did something differently? (If yes - what?)

Numeracy has been around for thousands of years (as we know from astronomers' and traders' records), so why was the mathematical compilation and analysis of medical results not considered in medicine until early/mid 19th (?) century. When did medicine change to become more science than art?

Still on numeracy & medicine: both ancient China and India had good understanding and respect for maths and conducted regular censuses. So, did either society incorporate math into its medicine, public health?

Re: "The Roman Empire and Indian Ocean: The Ancient world Economy & the Kingdoms of Africa, Arabia & India" by Raoul McLaughlin"

Thanks - will add to my reading list!

So, while I respect herbal medicine, I'm leery of self-medicating with it.

Don't those caveats also apply to that most-important herbal drug known as coffee...?

The leeway between useful and harmful doses of coffee is rather larger than with many things, though. And unless you drink it very strong, you'll get feedback on each cup before you have time to finish the next one :)

(And I suspect that the industrial coffee-making process reduces the variation in caffeine levels, at least for instant; grinding your own beans is another matter.)

Whoah, your second question is rather big and many sided. How much time do you have?

"Numeracy has been around for thousands of years (as we know from astronomers' and traders' records), so why was the mathematical compilation and analysis of medical results not considered in medicine until early/mid 19th (?) century. When did medicine change to become more science than art?"

There are different levels of numeracy though. Simple mathematics was widespread, but being able to make calculations for astronomy etc was a different sort of skill and often restricted in teaching. Plus you don't need complex maths for navigation for instance, you should look into that history.

Moreover, you are clearly taking a very modern viewpoint, and just not realising the subtleties of differences in thought between then and now. In order to have anything approaching modern epidemiology, a medieval surgeon, physician or other would have to not only be able to take and retain notes about individual cases, but meet many, many cases with similarities and differences. Then there was the lack of uniform training. You can take a modern approach only when you have a fairly uniform training, widespread means of transferring information about disease and illness and knowledge etc. So we're talking 19th century here.

Some people would probably argue that medicine became science in the 20th century, see also "The youngest Science" by Lewis Thomas, published in 1983, he was born in 1913.

Consider too that a lot in life can be done without making things submit to mathematical analysis. Huge cathedrals can be built without much more than geometry and simple measuring implements, no need for an engineering analysis. (And sometimes they got it wrong and bits collapsed)

So we're talking 19th century here 1854, John Snow, did the first mapping of cases in a Soho cholera outbreak and essentially invented epidemiology. I walk past his marker most days to get lunch :) As I understand it he was right at the end of the humours and bad airs movement but just before actual science.

See Star Trek IV aka Humpback to the Future.

While time traveling, Sulu gets a head injury and is taken to a 20th century hospital. They are about to drill holes to relieve the pressure as above, but Dr. McCoy turns up to denounce them as savages.

Comparing him to Dr. Pulaski in TNG, I wonder if Star Fleet Medical has a continuing education thing on how to be an arrogant jerk.

Yes, probably a complex history therefore good story fodder.

One example: Considering that betting on horses/camels has probably been around at least as long as medicine, the two (stats & med) must have intersected at least a few times. Then there's this ... as per Wikipedia: One of the origins of the word 'statistics' is "science of state" (then called political arithmetic in English). Basically, the potential for developing the field of epidemiology has been around a while. Why it took so long to be acted upon could be an interesting history lesson. Or did it ever gain any currency/usage within any region/era, but got killed off - why?

Ditto for horse/cattle-breeding, therefore awareness of inheritable medical conditions ...

Ah, but humans aren't animals. All the holy books and people's experience says we aren't, because we have intelligence and souls. Therefore breeding like animals doesn't work. Besides, that you got the same disease your father did was because his seed was corrupted, everyone knows that.

C'mon ... there must have been at least a few atheists through the ages ... or maybe a shy bookish monk who did double-duty as accountant and gardener at the local monastery.

There might have been, the problem if you are writing historical fiction with some fidelity to known historical stuff, is in finding them. On the other hand if you aren't, and are doing something more fantastical, then the boundaries are surely much wider.

My opinion is that a lot of modern people take for granted the sheer variety of viewpoints and ideas and structures of thought which are available just now compared to 700 years ago.

You have made me wonder how much information and ideas can be put into a fictional book from actual history, without it getting in the way of the story. Perhaps E. C. Ambrose can tell us more about how to decide what to put into the novel?

Theodoric of York - YouTube Video for youtube theodoric york medieval barber ▶ 4:39 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XHcgYlacYOg

best gag-

Martin: "Say, don't I know you?" Belushi: "Yeah, you worked on my back!"

@40: Yes, in addition to McCoy of TOS, Dr. Bashir of DS9 and the holodoc of Voyager were also at best acerbic, and I can't remember who the doctor of Enterprise was. Only Dr. Crusher (the main TNG doctor) had a warm bedside manner.

We know that a century in the future, novelists will write about medicine of our day, making sure to mention stuff which we think of as normal and which future readers will think of the same way as we think of bleeding. ... We just don't know which medical practices those are.

Most everything about drugs for mental issues.

Even if we're using "good" drugs just now our feedback loops are so primitive that we're killing ants with sledge hammers. In the wrong yard.

We have some effect but it seems not much better than chance. And things that do seem to work well tend to make the patient prefer the illness.

discussing this situation with a number of medical friends of mine convinces me that a large part of modern surgery is effectively just carpentry with expensive tools and very expensive nails.

For bone surgery, I'd agree. For others, not really.

Still on numeracy & medicine: both ancient China and India had good understanding and respect for maths and conducted regular censuses. So, did either society incorporate math into its medicine, public health?

I have to wonder how much could be done before we had data bases that could be complied and analyzed. And punch cards are a way to make a data base.

ST was always taking most of its subplots, character development, etc.. more from the year a show was made rather than the time it was supposedly set in.

Mini skirts in the 60s. Big hair in the 80s. Just two of women's fashions that infect the shows.

To all those people who are asking "why did the theory of the four humours persist for so long?"

Three major reasons: 1) speed of information transmission; 2) speed of data compilation; 3) human refusal to listen. Oh, and one over-riding one: the "scientific method" as a formalised system of inquiry is less than two centuries old. (Or in other words, you're dealing with a massive out-of-context error).

Prior to about a century ago, the fastest speed most information travelled at was the speed it took for one person to walk to another and tell them. Prior to even thirty years ago, the vast majority of people were limited to the amount of information they could access in their nearest library. In paper books, or paper journals. If you were looking for a particular paper, you had to hope the library you were looking in either had it in their collection, or was able to access it through another collection (but of course, first you had to know about that paper! Or that particular journal, or that particular field of study!)

It could take decades or centuries for an idea to become accepted even inside academic circles - decades which were mainly occupied by people who weren't certain about the notion digging up the research and the references, and essentially doing all that hard work figuring things out for themselves. Ordering in books and journals either by inter-library loan or from the publishers, trying to fill in the gaps where they couldn't access the particular piece of information given and so on - and possibly getting into contact with the original authors (if they weren't dead) to find out whether they'd heard of or read paper X which actually contradicted what they were saying?

So it took a long time for ideas to become established, and even longer for them to become disestablished.

When it comes to the speed of data compilation, again we're dealing with the fact most information didn't really travel all that fast, or all that far, or in a reliable format. So counter-examples wouldn't come back to bite a theorist on the backside until well after they'd published the original theory and gained their credentials. It was hard to ascertain the veracity of counter-examples, and it would take a lot of time unless you're getting your counter-examples from a known reliable and trustworthy source. At which point we come to our third factor...

Never disregard human psychological insecurity as a reason for otherwise unreasonable behaviour. A successful physician who has been granted a degree by a university (which, at that time, was essentially the academic equivalent to a knighthood, or a captaincy in the army - think of the saying "a lord of high degree" to describe someone very high up the social ladder) isn't going to listen to a mere barber or surgeon telling them they're wrong about their theory. The theory of the humours came down to mediaeval writers from Galen, who was one of the Romans - it had the force of authority behind it, and these were rather authoritarian times, where people were raised up effectively from birth to respect the words of ancient thinkers and their overlords over the words and actions of ordinary people (consider: the Catholic church was the over-riding unifying power of Europe, providing continuity and stability through the legacy of the Roman empire that it embodied).

In order to dislodge the theory of humours (which didn't happen until comparatively recently, as guthrie points out) you need a lot of evidence compiled from a lot of places, covering a lot of cases. You also need the belief that firstly, knowledge is mutable, rather than fixed (that it isn't revealed, but rather accumulated, and that what we know can change over time); and that evidence has value in the accumulation of knowledge alongside theory. Neither of these pre-conditions were met until the wide-spread acceptance of the set of values we think of as "Enlightenment" values - prior to that, knowledge was revealed by or to the knowledgeable, evidence wasn't valued, and so long as you theory sounded good enough to hold up to cross-examination by your peers, it was considered worthwhile.

Incidentally, one of the reasons I tend to get a bit annoyed with the people who are chasing the technological Singularity is because I think we're actually living at the end of a Singularity event already: the entire period of the Industrial Revolution, and the centuries following, have been one great big singularity, in which all is changed, changed utterly. One of the biggest symptoms: the near-inability of a lot of people in the modern day to understand just how much things have altered, even within their own lifetimes.

What Megpie said.

As an illustration, in 13th century England, Daniel of Morley, iirc, was asked by his bishop to write a book about the four elements and how the universe was, because he'd spent the previous few years in Spain doing translations of the new imported learning.

At the same time though it is important to recognise that people did learn and innovate in ways not unlike now, and new information did spread around. For instance distillation of wine to make medicines became widespread amongst physicians etc from the late 13th century onwards, across Europe, although of course you are talking about a couple of generations to become widely known and established. Or look at the spread of theriac or books of secrets.

the "scientific method" as a formalised system of inquiry is less than two centuries old Err, no - it is considerably older than that. You are positing "scientific method" as being, effectively post 1815 (??)

Francis Bacon died in 1626 Harvey's published on blood circulation: 1628 Foundation of the Royal Society: 1660-63

So almost 400 years old. Unless you want to start with William of Ockham (!)

However, regarding our present on-going Singularity, you are singing a song I've already sung & fully agree with; Writing, Steam Power, Electrical power, Computing - after each of those steps, the world changed.

You might not believe this, but there is a difference between science (1640) and science (1850) and science (1930). Just go and read some modern history of science works.

Also, Ockham's razor definitely isn't science. If you want something more like science, look at Pope John 22nd and his enquiry into alchemy in 1322 or so.

I think the other singularity that most people don't know about or ignore, hence brexit, it globalisation. Suddenly everything comes from another part of the world, and it confuses them.

Other interesting (for the usual values of "interesting") side effect of the ongoing singularity -- highlighted by Brexit and the Trumpening -- is the inability of many to understand that "bring manufacturing back" won't bring jobs back.

The split between Rationalism (the idea that absolutely everything possible can be predicted and calculated given an initial condition, if you think about it long and hard enough) versus Empiricism (the idea that you might need to check your conjecture against material evidence, which could be qualitative or quantitative) was still going strong well into the 19th century, too. The "quantitative" part had led to a bunch of technologuies by then which even the most committed Idealist (NB also not a word that always means exactly what it might in the everyday sense widely used now) could never have predicted. So it had become mostly a non-debate by the time of Heisenberg. (I don't mention Kant here for several reasons that are not part of the main point).

Long story short, we're all empiricists now and big-R Rationalism is mostly forgotten, with the term being re-used for something almost but not quite opposite to its old meaning. What we were taught in school as the Scientific Method is mostly a string of rules of thumb derived from the notion of checking rationalist theory against empirical measurement (or at least observation).

There are some interesting implications that do not generally align well with "common sense" views, but nonetheless are worthwhile exploring. Evidence does not need to be "objective" or quantified to be empirical, it can be either or neither. Questionnaire surveys are all about quantitative subjective evidence. Individual data points can be derived through a subjective and qualitative process, then combined with others to form a quantitative model. Quantity based on measurement is often much less reliable than we credit, and understanding why one might draw a distinction between precision and accuracy is really important. We live in a (sort of Kantian) synthesis of these mode of understanding, working with it all the time.

Whereas in the 18th century some academic colleagues might have argued that going so far as performing experiments simply meant you weren't thinking hard enough. Or long enough. Or bell-shaped enough or something.

"Re: "The Roman Empire and Indian Ocean: The Ancient world Economy & the Kingdoms of Africa, Arabia & India" by Raoul McLaughlin"

Thanks - will add to my reading list!"

Ditto, since the only book I have specifically covering that is Mortimer Wheeler's 'Rome Beyond the Imperial Frontiers', which is now 60+ years old, so certainly much overtaken by newer discoveries & insights.

That's an easy one: statistical science, particularly that involving cohort studies, evolved from actuarial science. Which, in turn, was developed in response to the creation of risk-based insurance premiums which apparently date to the mid-18th century.

There's also a big dose of probability which arose from studies of gambling and the development of the enabling calculus.

Selective breeding, whether of animals, plants or microorganisms, can proceed quite nicely without any concept of science or mathematics. It's merely allowing the desired organisms to reproduce while destroying the ones that are not desirable.

Numeracy as such isn't the issue. You have to have a rationale for applying the numbers. That means probability and statistics. Probability theory was primarily the creation of Blaise Pascal in the 17th century, and his original focus was gambling odds. And initially he was somewhat in the dark; years ago I copy edited a translation of one of his early essays where he was trying to figure the odds of different rolled totals on two six-sided dice, and got it wrong (by treating, for example, 1 2 and 2 1 as the same outcome, instead of two different outcomes with the same total). Of course he corrected it later, but it wasn't instantly obvious to him.

As for statistics, I believe it comes from roughly the same time period. But originally it was state-istics, literally: The collection of numerical information relevant to state policy. The first application to anything medical was the work on causes of death that was reported to the Royal Society during the reign of Charles II, which gave rise to the life insurance industry. The time from that to comparing the effectiveness of different medical procedures was maybe a century and a half, which is a bit slow but notthing compared to the time from the first invention of written numbers.

If we're going to ask why the four humors lasted so long, we should also ask why the four classical elements lasted so long, as the four humors are just a physiological analog of that theory. The idea of fire as an element ("phlogiston") persisted up till the late 1700, when Lavoisier proposed the oxygen theory of combustion. Chemists had been wondering about phlogiston ever since they figured out how to apply the balance to chemical reactions and discovered that metals (which had been "phlogisticated") weighed less than metal oxides (from which the phlogiston had been "driven out"), which suggested that phlogiston had negative weight—but that had been only around a century, I believe.

Really, a huge share of the scientific knowledge we take for granted dates to the eighteenth century or later, hardly the blink of an eye in historical terms.

Except that the four "Elements" was true, just not (at all) in the sense in which it was first envisioned.

Four "Elements" = Four states of Matter Earth = Solid Water = Liquid Air = Gas Fire = Plasma

No wonder the ancients were confused.

^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^ IIRC, didn't K S Robinson play with this in his "Mars" trilogy?

Regarding the speed of change: I'm old enough to have seen quite a bit of it. Just one small example:

In the period 1977-79, I had the privilege of some access to Cambridge University's main research computer, a rather high-end mainframe. It cost around £17 million in 1970s money - maybe ten times that now, there were a few years of very high inflation - and the main hard disk stored 105MB (if memory serves), took several kilowatts of power, was the size of a large industrial fridge, cost about a million pounds and weighed about a ton.

Last week, I had the somewhat frustrating experience of looking for a 64GB memory stick I'd lost down the back of the sofa. It cost me about £15; that much memory when I was in uni would have cost about half a billion (if you could buy it!) and filled a small office block, easily - and God only knows how much it would cost to run.

Another: When I started work, photocopiers were rare.

I still have my slide rule, and occasionally use it when I can't find my calculator.

I remember programming an old computer at university where you still used face-plate switches to load the registers.

problem about established authority... Aristotle said that flies had 4 legs... no one bothered to check for about a thousand years

Not really; he had his psychiatrist character use the four humours as shorthand labels for the far points of a two-axis (labile/stable, extraversion/intraversion) graph of personality types.

Re: numeracy and stats

Sometimes think that stats is the poor-man's math, just like geology is to physics. Algebra and geometry were always bigger deals to my math teachers until my undergrad where in some subjects if you couldn't attach any stats or do any stats testing, then you had nothing! For me, stats is the silent partner of science ... sooner or later you have to test your results and this typically means checking the numbers.

Back to medicine ... have been listening to/watching news shows talking about the aging demographic and how expensive it is for society to treat this segment. What I've never heard is: thank gods we have a glut of oldsters that are medically and scientifically naive and who are also willing guinea pigs lining up to try/test various new and old meds and procedures so that their kids' and grandkids' health can be better, and their medical and psychiatric conditions more efficiently and more cost-effectively treated.

Early vs. modern communications - okay, physical communication was pretty limiting in the olden days but (I think) it was made up for by the frequency and regularity and sheer volume of written (therefore trackable and verifiable) communications. Some time back read about Darwin and Wallace and was struck by how their awareness of each other's thoughts was pretty close to real-time despite the slowness of their era's communications vehicles. Ditto for other famous correspondences re: races to publish or rivalries about theories.

From an SF/F perspective, I think it might be possible to contrive a meeting of a math-savvy Arab and a visiting/touring western medico (probably a Knight Templar) possibly as far back as the Crusades. The Arabs traded regularly with more eastern parts so would have had access to whatever was going on in India and possibly as far away as Korea and China. (Wonder how an abacus could be used to do stats testing; maybe a foldable version that lets you see z's/sigmas right away.)

Actually, re. your fictional suggested meeting, real life is stranger than fiction. For instance, there is a record of an ex-jew appearing in Bremen and offering to turn copper into gold:

https://www.alchemydiscussion.com/view_topic.php?id=526&forum_id=8&jump_to=2403 in 1063.

See also Sicily and the court of the Emperor there.

Basically there were much more communications and travel than random knight meeting Muslim physician, that's so simple stuff for simple hollywood films.

Your key text in understanding herbalism as it relates to the modern pharmaceutical industry is Trease and Evans' Pharmacognosy, now in its 16th edition (when I was a larval pharmacist it was in the 13th edition). Note: it's not cheap, and it wasn't cheap back then, either!

Pharmacognosy is the study of drugs (in the pharmaceutical sense) of botanic origin. Not so much "herb X is good for condition Y" as "the following species express alkaloids A ... M in quantities ranging from N to O percent by dry weight, which can be extracted by the following process ..."

As of the mid-eighties about 50% of the drugs on the market were either of botanic origin (heavily processed and purified) or, more frequently, synthetic analogs of alkaloids, flavonoids, terpenoids, or other chemicals first isolated from plants that had a history of being used in herbal medicine.

That would be "true but not in the sense that it actually describes reality"?

It seems to be fairly common in the sciences that you start out with a theoretical model that reflects common sense or intuitive impressions: geocentric astronomy, impetus mechanics, phlogistonic chemistry, or mercantilist economics. And then you formalize it and try to apply it systematically, and that forces you to develop a new theory that avoids the incongruities of that initial model. But the idea of the four stoicheia wasn't even such an initial theory; it was more a descriptive language than a source of predictions.

Re: 'Trease and Evans' Pharmacognosy, 16th edition'

Thanks, Charlie!

Already looking for a deal on it ...

Excerpt from book description below. Interesting stuff ... including who'd have thought that BrExit might affect access to this type of info.*

'New to this Edition

New chapter on 'Neuroceuticals'.Addition of many new compounds recently added to British Pharmacopoeia as a result of European harmonisation.

Considers development in legal control and standardisation of plant materials previously regarded as 'herbal medicines'.

More on the study of safety and efficacy of Chinese and Asian drugs.

Quality control issues updated in line with latest guidelines (BP 2007).'

GMO not specifically mentioned in the table of contents - rather surprising, that.

Was this dude accompanied by a rooster, cat, dog and donkey?

I don't think so. Magic is not my main focus of research, but I've read a bit here and there, and IIRC that sort of symbolism is more from the Mediteranean and Arabic magic, which just hadn't gotten that far north at that time. 200 years later, yes, but not in 1063.

I do hope we haven't scared off Ambrose!

It wouldn't be so hard to contrive a West/Islam meeting in the 1340s, or even see Islamic influence. Spain is not so far from England. The work of the Toledo School of translators in the 12th & 13th centuries meant that some Islamic works were part of university curricula throughout Europe, or even more generally available e.g. Chaucer's Treatise on the Astrolabe was drawn from the Latin translation of a work by Messahalla (Masha'Allah ibn Athar). Physicians and maybe Surgeons would be taught from Avicenna's medical books, among others. Would a barber-surgeon be familiar with them?

In southern Spain The Emirate of Granada (covering what is now Malagla, Granada & Almeria provinces) would stand for another 140 years. Unfortunately Elisha is about a generation too early to be involved with The Black Prince or John of Gaunt's intrigues in Castile.

Lastly, Jim Al-Khalili's three part BBC documentary 'Science and Islam' is worth watching. Not on iPlayer, but can be found through the usual other places.

Re: 'Jim Al-Khalili's three part BBC documentary 'Science and Islam''

BBC certainly produces excellent documentaries ... Thanks for recommending! The entire series is online ... look forward to watching it.

BBC Science and Islam 1 - The Language of Science https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FLay7RD3kEw

BBC Science and Islam 2 - The Empire of Reason https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oUGBp_mKrkI

Science & Islam: Part 3 [3/3]: The Power of Doubt [Comparative Study] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7B7kh5jPhno

Re: 'I do hope we haven't scared off Ambrose!'

Agree ... hope that it's because she has a life offline and not because we're scary or boring.

Of interest might be Michael Flynn's short story "Quaestiones Super Caelo et Mundo". It appeared in Analog about a decade ago, so might be hard to track down. Alternate history where the scientific revolution kicks off early in Paris because of a translated book in Spain.

Only if you restrict yourself to those states of matter and ignore the others, such as Bose Einstein condensates and the like.

(I take it as special pleading to be honest.)

The 4 states mentioned are, of course, "classical". Quantum states would have been completely unknown & unimaginable -then. It's quite hard enough getting one's head around the problem, even now ....

Yes, that's why it's a bad idea to start drawing connections or analogies between the classical stuff and modern ideas. Unless you are doing art.

And, of course. Spock's regular comments about McCoy's "beads and rattles"...

Enterprise - Dr Floxx (sp), who was an alien with a "can do" attitude and a collection of natural remedies derived from assorted creatures.

Ahh, the butterflies of the trouserlegs of time. Yes, the July 2007 Analog. Doesn't seem to have been reprinted, though it picked up a Sidewise and an AnLab award. Luckily I've got Analog back to 1950, so I've thrown it on the top of the (re)read pile.

PS anyone know where to get copies of Spectrum SF #1-3? I only bought it from #4 on, back when I lived in the UK

PPS - EC - going to get the first of the series - medicine, middle ages, mystery & magic? That's worth a go.

Wow,I get snow-bound for a couple of days and you guys totally run with it! That's awesome. (do you have roof-rakes in the UK? Let me tell you, being on a ladder in a wind-storm trying to pull icicles off a three-story house = not much fun)

I don't think I'll be able to catch up with all the questions/ remarks above. Please accept my apologies for vanishing--that was not my intention.

I wanted to thank the commenter above who tracked down the remark about trepanation being used to let out demons--I have been searching my notes (many of which are currently, alas, in storage). so I am pleased to stand corrected in the particulars. What had struck me when I ran across that reference is that so many people will cite "letting out demons" as the reason for trepanation--but if actually look at the medical references, I can't find anyone in the Middle Ages who recommends it for that purpose.

re: the role of numbers and statistics in medicine in China or India. . .while I have been delving into historical China for another project (1200's, primarily, during the Mongol invasion), I was intrigued by the observation that the Chinese, with their very long established bureaucracy and at times obsessive record-keeping, probably do have records of all sorts of interesting things that we in the West don't have access to. Much was destroyed during the Cultural Revolution, unfortunately.

Joseph Needham collected thousands of documents and began compiling Science and Civilization in China (a project that goes on to this day). Those works may have some information for those who are interested. The institute bearing his name can be found here. so that might point you to some more specific resources.

I was struck by the fact that the oracle bones of Shang era China (animal scapule and turtle shells used for divination purposes) not only are inscribed with notes about the prediction, but also include follow-up notes from later times about whether and in what way the predictions came true.

re: choosing what to include.

This was tricky. The choice of a barber as the protagonist, and the fact that he almost immediately goes to war, means that, for example, the theory of the four humors gets pretty short shrift in the books. It was a huge part of medieval medicine, but mostly at the higher levels--dealing with illness rather than wound-healing, physicians rather than barbers. It is mentioned, and plays a stronger role in some of my short stories around the characters.

I also made Elisha a skeptic. He's been disillusioned about God, and authority figures in general, due to an early experience with a witch-burning. As a result, he tends to believe the evidence of his own eyes and the skill of his own hands instead of what the learned men tell him to believe. When a carter tells him that a relation was cured of a curse by bathing in mother's milk, Elisha's response is 'that sounds expensive.'

Historical fiction is always a balancing act between crafting a satisfying, engaging story for the reader, and still maintaining the sense of the time. Does Elisha's skepticism make him less medieval? As some have remarked above, even during periods of wide-spread shared beliefs, there are always those who fall to the outside of those beliefs. One of my beta readers remarked that she had assumed Elisha was an atheist, but there is a difference, I think between a contemporary person of today proclaiming themself an atheist, and a person raised and steeped in very long-standing and extremely entrenched Catholicism turning away from God. It's not that he doesn't believe in God, but rather that he doesn't trust him. Early on, someone asks Elisha what he does have faith in (if not God or established medical authority) and he displays his own two hands.

So in selecting what was included and what was left out of the books, I was strongly guided by Elisha as my protagonist and sole point of view character. What would he know and experience? What would most challenge him physically and psychologically? And yes, sometimes, what is just so cool/fascinating/disturbing that I can't possibly leave it out?

Sometimes that made it tricky to convey the full reality of the historical setting. Part of what I enjoyed in writing the series has been expanding Elisha's own perspective. As he grows in power and understanding, he sees more about what's going on around him and is exposed to more of the complexities of the larger world.

A lot of the comments about "medievil demons and witches" I think are actually later grafts onto Christianity as it became a method of controlling the population.

Catholic CHristianity in Europe in the 11th and 12th centuries was struggling with the mass of common folk belief and sort of magic ritual stuff that wasn't theologically illegal at the time but was later on. Over the centuries they hammered out doctrine and ideas which resulted in banning of most of what we could call magic, and of course various interal arguments. Then later on after the reformation the death of magic as a commonplace thing was down partly to the forceful opinions of protestants who regarded it all as mere superstition.

Re: 'Catholic CHristianity'

Meanwhile in India, Christianity got mixed with Judaism and Buddhism, with a dash of Hindu customs for good measure (i.e., sucking up to the higher caste) and some Indian Christian sects trace back to about 60 AD (St Thomas Christians). For some reason I think of David Eddings whenever 'religion gumbo' comes up.

Have noticed that it's harder for me to get into and stay interested in novels that have non-European/non-white North American mythos as their backgrounds. Maybe it's because even a tiny dose of the mythos I'm familiar with will immediately surge up tons of tacit learning to flesh out the plot, characters, etc.

I can't think of any specific quotes just now, but I have read of various medieval people expressing unorthodox views about religion. Some were Wycliffites of course.

Ah hah, I just remembered the book.

See "The materiality of unbelief in late medieval England" by John H Arnold, in "The unorthodox imagination in late medieval england".

There's also Roger Bacon (13th century) - English Franciscan, philosopher, scientist and scholar famous for challenging blind acceptance of widely accepted writings including Aristotle's. (A few others from history of moral philosophy mostly.)

Let's face it, quite a bit of blurring between the teachings of the ancient Greeks and the interpretation/emphasis on select bits of the Old Testament as the lens through which Christian sects understood the physical world, Man's temperament and Man's relationship with God.

That's an interesting point re. your filling in the implied and actual gaps when reading stuff with familair sources. I've certainly found it a bit tricky at times to grasp Japanese or Chinese cultural nuances in manga etc.

If you're interested in Bacon, you might like to read "Roger Bacon and the Sciences" edited by Roger Hackett.

Two quibbles that in no way detract from the value of what you've written. First, all of this depends on the historical period and region (e.g., compare Christian Europe vs. Moorish Spain). Second, in any population of professionals, a majority is likely to stick with established doctrine even in the face of mounting evidence that the doctrine is wrong or incomplete or ineffective; there's usually only a minority (often a small one) willing to challenge authority and establish a new paradigm. That diversity is often omitted in discussions of medicine, science, and other social phenomena.

In terms of herbal medicine, this has long been known to be effective: examples include "Jesuit's bark" = Peruvian cinchona, which was significantly effective against malaria; the abovementioned salicylic acid = from willow bark = aspirin minus the acetyl group that makes it less harsh on the stomach; foxglove extract = digitalin = cardiac meds; and (if you're willing to include fungi as herbs) moldy bread used as a poultice that contained significant amounts of penicillin = Penicillium spores and hyphae.

The problem with herbals has always been how to achieve a reliable dose that is neither too low to be therapeutic nor too high and therefore toxic. It's not easy to do that even today; imagine how tough it was before real chemistry was invented. And concentrations vary between plants in a given year, between years, and between regions. Then there's that inconvenient variation in how individual humans respond to a given drug. We're only now starting to do serious work to tailor the drug and concentration to each patient's genetics.

guthrie repeated a frequent misunderstanding: "Also, Ockham's razor definitely isn't science."

Ockham's razor is also referred to as the principle of parsimony, and it means that you shouldn't make things more complicated than necessary. That is, only if the simple explanation doesn't work should you look for a more complex explanation. It's not science, per se, but it's a perfectly reasonable principle to include within the scientific toolkit because science advances very efficiently by buildign a bunch of simple explanations into larger and more complex explanations.

SFreader noted: "There's also Roger Bacon (13th century) - English Franciscan, philosopher, scientist and scholar famous for challenging blind acceptance of widely accepted writings including Aristotle's."

Possibly one of the most important points promoted by Bacon and his colleagues was the Englightenment notion that reality could be understood based on the evidence of the senses rather than relying on divine inspiration and dogma handed down through the generations. (See Bacon's Novum Organum, as a direct challenge to Aristotle.) They also promoted the notion that knowledge could be systematized. Therein lie the origins of modern science. Needless to say, the reality is far more complex than my 20-word non-expert's summary, but the summary points in the right direction.

I don't think I misunderstand at all. By science I mean the overall practise, usually typified by theory, experiment and feedback thereon. Occams razor can as you say be a tool in the overall endeavour, but in the context of the time that we were discussing and indeed modern science, it isn't science.

Then later on after the reformation the death of magic as a commonplace thing was down partly to the forceful opinions of protestants who regarded it all as mere superstition. This is why, of course, the accusations of witchcraft were so prevalent in Protestant societies, of course (! ?? ) James VI & I, the Witchfinder general, Salem, etc. Oops

Just to add to the fun I asked on Twitter if Occam's razor was science, part of science, or a useful tool in science, and a historian of mathematics replied "Philosophy".

I think you're cutting too narrow a path. The Inquisition made the Protestants look like amateurs.

The Inquisition wasn't much for witch-burning; its main pursuit was ferreting out heretical sects and backsliding converts (broadly defined). The office that prosecuted Galileo was much more interested in your belief in the sacraments than your interest in magic.

Re: ' ... the notion that knowledge could be systematized.'

What evades me is how they attempted to 'systematize' if they didn't have or collect statistics. This also relates to (my understanding, not sure if it's fact) that some of this systemization was: "If all examples you can think of fall into this category, then such-and-such is true. If not, then your premise is false." So, basically, an all-or-nothing style of reasoning/dogmatism still around today. Don't remember if classical, syllogistic logic had any way out to resolve this type of argument.

Was this the era when academics/philosophers almost completely disconnected from the common rural folk to become predominantly city dwellers? Because as any farmer can tell you, breeding does not always run 'true' ... therefore an all-or-nothing approach to reasoning/explaining is fantasy.

Anything - adage included - that's been around long enough can probably find a spot in the 'philosophy' niche. Philosophy was a catch-all term and covered lots of subjects.

Correct (ish) It was HERETICS who got burnt alive by the RC church. How nice.

And by the protestants, I believe. Also it was usually heretics who recanted their original confession and abjuration of heresy. They can't say they weren't warned.

As for Galileo, it' much more complex and interesting than the pop-sci view of it, and people should stop pretending it was all so simple:

https://thonyc.wordpress.com/2014/05/29/galileo-the-church-and-heliocentricity-a-rough-guide/

He's more just lightly trolling. The fun thing about the medieval period is that Theology is Queen of the sciences, as I read in Bacon's Opus Majus.

While I've not read Guest Host's work (too close to home & some vicarious experiences), while I'm munching through the teaser chapters, just a tiny nod of appreciation. +10 Kudos for differing discussions / content on various blogs, kinda flattering to see it wasn't just a copy/paste drive.

Also, tickled by this:

The friar’s description of the ugly monk he had received them from matched Morag himself: apparently the mancer had a sideline in passing off parts of soldiers as relics of saints. Without participating in the death himself, Morag couldn’t use these as talismans, so he seemed to have found another way to profit by them.

This amused me a little, since, you know, exactly which parts get made into relics is left to the imagination: Non sfrocoliate la mazzarella di San Giuseppe!

Stop Pestering St. Joseph’s Genitals! Neapolitan sayings.

And yes, that was inspired by the font choice of her/zer work.

What evades me is how they attempted to 'systematize' if they didn't have or collect statistics.

"Data is not the plural of anecdote" is a fairly recent thing. You can have systematic observations without statistics, Linnaeus for example. I'm not sure he ever saw a black swan, but if he did he'd have no doubt that it was a swan. Much as if I ever see a white one...

I suspect that back in the day the early libraries had some from of organisation more sophisticated than grading documents by size or colour. There was also considerable synthesis going on, trying to fit bits of knowledge from different sources into a coherent whole.

I suspect people have argued vigorously about when that transitioned to a formal methodology, but the little I know of the history of libraries is fascinating.

NOT in England, at any rate. Catholics were killed by the judiciary, but they were killed for "civil" offenses & never burnt. This may have been/was different elsewhere, as in "Give'em a taste of their own medicine". I certainly know that very nice man, the ultra-protestant Jean Calvin had people burnt alive.

Actually, I had an interesting experience with a Chumash healer once. She'd apprenticed a USC pharmacology professor who was interested in the active compounds in her herbs, and they did really cool lectures back in the day. Sadly she died in a car accident years ago, but he's still around and working with the tribe.

Anyway, about the variation in plants. She knew that and exploited it. With white sage, for instance, she had over 400 different collecting sites (possibly individual plants) across southern California and Baja, based on the differences in the effects of individual plants.

This kind of knowledge is common in the horticultural community, where they make clones (we know them as selections and/or cultivars) of plants with useful properties for our gardens. It doesn't get seen so much in academic botany, which is typically focused on populations, species, and above. The problem is that medical science spends more time talking to the botanists than they do to the gardeners, so they're not quite so aware that yes, some people do recognize and use within-species diversity in herbs.

This kind of knowledge is common in the horticultural community

The legal community is also well aware of it, and so will you be the day you start claiming that your fizzy wine is "Champagne" because it's made using that cultivar :)

As it happens Heteromeles is in the US, where local producers quite merrily make Chablis and Burgundy and yes, even Champagne. They just have difficulty exporting it under those names.

(Real Champagne may be entirely Chardonnay, or entirely Pinot Noir, or composed of other cultivars. And then there's Zinfandel/Primitivo for cultivar confusion.)

Heteromeles noted that "[a native healer he met] knew [about [about the variation in plants] and exploited it. With white sage, for instance, she had over 400 different collecting sites (possibly individual plants) across southern California and Baja, based on the differences in the effects of individual plants."

That's important, but the variation also exists at the individual level between years. A specific example I can provide (based on the genetics paper I'm editing today) is anthocyanins, which are the chemicals that create coloration in grape skins. The same plant can have high levels of these compounds as a result of a cold but sunny veraison (ripening) period, but low levels with a warm and cloudy season. The color change is an obvious cue, since it is roughly proportional to the anthocyanin content (though the hydroxylation and methylation of these compounds varies), but in other plants, the changes won't be externally visible. I imagine that for some plants, a taste test or smell test would provide some insights into the dosage, but not quantitative ones.

One tremendous advantage of modern pharmacology is that there are powerful techniques for standardizing the dosage. That makes all the difference when it comes to achieving reliable effects.

If anyone is still reading, probably the best one volume introduction to the topic of later medieval medicine in England, is called "Medicine and society in late medieval England" by Carol Rawcliffe. It was published in 1995, but I haven't heard of a better one since then. "Dragon's blood and Willow bark" by Toni Mount is much more recent, but pitched a lower level and I found a wee error or two in it.

"Given the number of of medical concerns that will work themselves out without any intervention, ..."

Including some quite severe ones, like most infectious diseases and even some broken bones. And you can ignore quite a lot of pain if there is no option and you are busy. People accustomed to modern medicine often miss those aspects.

"Medicine and society in late medieval England" by Carol Rawcliffe

Carole with an 'E' if yo don't want Amazon saying "Nah mate, never heard of her".

Hardback, VGC, £1.67, one copy left... Sold.

Geoff, you do have to be very careful about herbals being "known to be effective". We can pick out some nice examples like willow-bark and quinine, because we know what the active ingredients are and where they come from. But even a blind darts player will hit the board a few times if he throws enough darts. And boy, did those guys have a lot of darts. Basically, if you could chop it off or dig it up then it got labelled as the cure for something.

Chinese herbal medicine is perhaps the best example of this. The number of things claimed to be cured by bits of ground-up animals is legendary, and all of it is complete bunk. And if you have the misfortune to be stupid enough to visit one of them these days, chances are (from a very large set of raids a few years ago) that what you'll actually be getting in amongst the ground-up leaves is illegally-high quantities of steroids.

Back in Europe, we have feverfew and eyebright which don't affect fever or eyes. We have a myriad claims for St John's wort, lavender, elderberries and dandelions, almost all of which don't stack up or at least would only work with modern extraction methods for the compounds involved. We have things like comfrey, which used to be used for tea but which we now know is actively toxic unless you're really careful (like laboratory precision, not "three spoons or four in the pot, mother?"). Mouldy bread will mostly not produce penicillin - mostly it just goes mouldy and infects you. And the less said about cow shit poultices, the better.

Everything we know about magnets, crystals, homeopathy and all the rest of that bunkum tells us that people will always associate doing something with getting better, even if what they did had no effect. Add placebo effect to that, and it all goes very wrong.

So the reasoning that "some of these compounds came from herbs, therefore old herbals were correct" is very, very wrong indeed. Not just that, it's actively dangerous for all the mugs who see "herbal" or "natural" as a good thing.

That reminds me, last year I tried making a spreadsheet of herbal cures for illnesses, against the recipes suggested by John of Rupescissa*, and although I didn't get into it much, it immediately became clear that there was a wide variety of herbs used for the cures, not the same ones for the same illnesses.

Graham noted: "Geoff, you do have to be very careful about herbals being "known to be effective".

Yes, to be clear, I was not in any way implying that all or even a majority of herbal remedies were effective. Just trying to make the point that some did work better than random chance and better than the old joke about headcolds*, and some really did work almost as well as modern drugs.

It's also worth noting that modern pharma doesn't have an unblemished record either. A great many modern remedies seem very promising at the start, and then turn out to be useless. Nutraceuticals such as vitamin C and omega 3 fatty acids, for instance. The main difference is that modern scientific techniques greatly increase the rate of successful discoveries.

I'n not quite old enough to remember Pauling and megadoses of vitamin C, but I think it's a bit unfair to blame modern pharma in general for vitamin C and omega 3. Better to discuss the story of mental health medicines and the various testing fuckups.

Having said that, one thing that is surely common between medieval and modern medicine is that there is a core of well educated doing the best they can people, with a great many hangers on, bottom feeders and con men trying to make a quick buck off desperate people, and the last 3 are the ones who push amazing wonder cures like vitamin C and fish oils so much for so long that people will get the idea they are great.

For those interested in Roger Bacon, I remember James Blish's novel 'Doctor Mirabilis' with fondness (though I haven't read it since my 20s - it's in my "reread" stack but I haven't found the time yet).

You mean, like mint or ginger for stomach upsets?

One thing to realize is that different plants have similar chemicals. Another thing to realize is that things like tannins can be good for stopping blood loss and a few other things, and tannins are a common defense chemical.

As one herb book I have noted, "how many stomach upset remedies do you need to have available?" The implication was that there's a bunch, and if you're a working herbalist, you only have to know the ones that are available locally and effective. In our case, that's things like mint tea, antacids, and proton pump suppressors available from the local market. In other cases, that might be ginger, mint, chamomile, etc.

Thanks! - Blish's Cities in Flight is a favorite. For those unfamiliar with it, it's essentially four novella length stories covering different eras/steps in the the evolution of independent city states in space. Here's the brief description of the first story 'They Shall Have Stars' ... kinda familiar-looking this stuff just now.

'2018 AD. The time of the Cold Peace, worse even than the Cold War. The bureaucratic regimes that rule from Washington and Moscow are indistinguishable in their passion for total repression. But in the West, a few dedicated individuals still struggle to find a way out of the trap of human history. Behind the screen of official research their desperate project is nearing completion . . . '

Re: Vitamin C

Recall that a few years back some research showed that VitC when correctly administered is effective for some serious conditions. Also recall how much razzing Pauling got for pushing VitC as a potential cancer therapy. Turns out both sides were right: VitC is not a cure-all but VitC intravenously administered at the correct dosage can help 'cure' certain cancers. What's really interesting is that Pauling probably made his claim about the power of VitC based on test-tube level research: VitC can kill cancer cells in vitro. Unfortunately all early VitC cancer therapy tests with humans were done using orally administered VitC which basically did nothing (no cure). Anyways, it turns out that both the form of the VitC as well as how the treatment is administered matter.

Wonder how many other potential cures/treatments have been incorrectly put aside because of similar methodological or piddly details.

Still-official stance:

https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/treatment/cam/patient/vitamin-c-pdq

The 'maybe it works' stance ...

http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/cancer/expert-answers/alternative-cancer-treatment/faq-20057968

Excerpt: 'More recently, vitamin C given through a vein (intravenously) has been found to have different effects than vitamin C taken in pill form. This has prompted renewed interest in the use of vitamin C as a cancer treatment.'